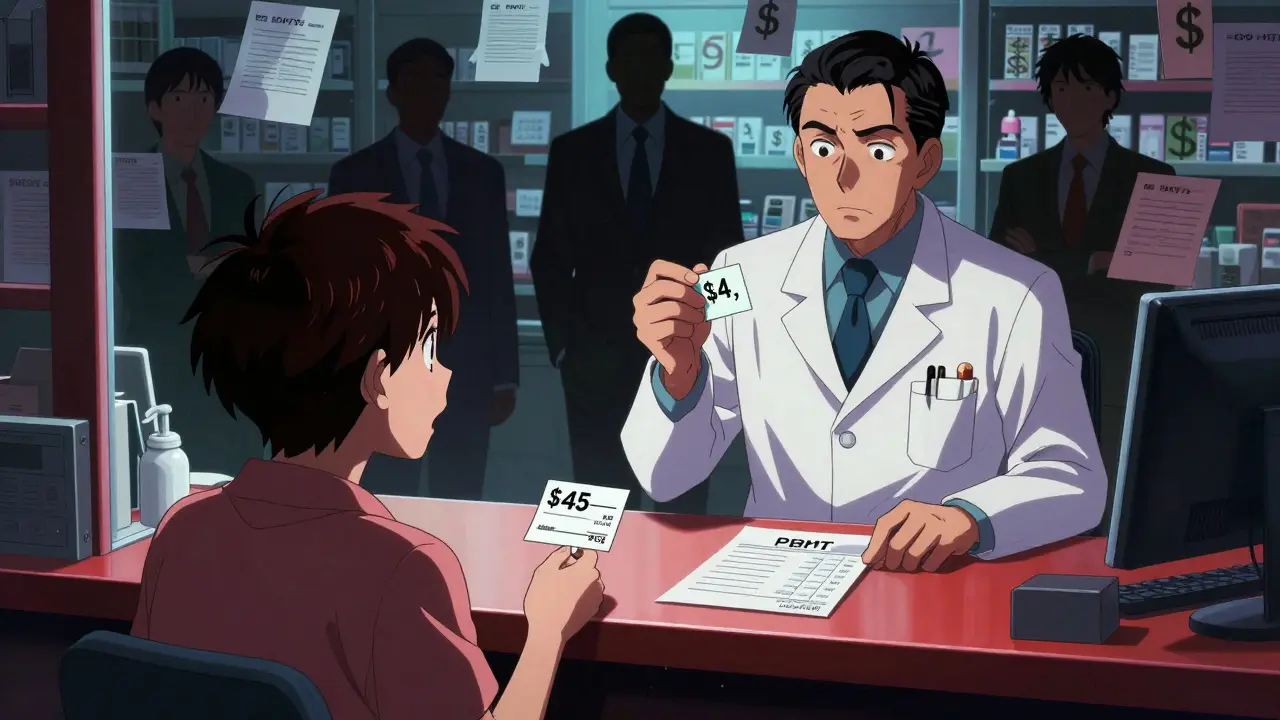

Most people assume their insurance covers generic drugs cheaply-after all, generics are supposed to be the affordable alternative to brand-name meds. But if you’ve ever been surprised by a $45 copay for a $4 generic pill, you’re not alone. The truth is, generic drug prices aren’t set by pharmacies, drugmakers, or even insurers directly. They’re the result of complex, hidden negotiations between Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and pharmacies, with patients caught in the middle.

Who Really Controls Generic Drug Prices?

The real power in setting what you pay at the pharmacy doesn’t lie with your doctor, your insurer, or even the drug company. It’s held by Pharmacy Benefit Managers-middlemen companies like OptumRx, CVS Caremark, and Express Scripts. Together, these three control about 80% of the PBM market in the U.S. They don’t sell drugs. They don’t fill prescriptions. But they decide which generics are covered, how much pharmacies get paid to dispense them, and how much you pay out of pocket. PBMs negotiate with drug manufacturers for bulk discounts, then strike deals with pharmacies on reimbursement rates. These deals are buried in contracts full of jargon, secret formulas, and clauses that prevent pharmacists from telling you there’s a cheaper way to pay. That’s called a gag clause-and 92% of PBM contracts include them, according to CMS data.How the Pricing System Actually Works

Here’s how it plays out in practice. When you hand over your insurance card for a generic drug like metformin or lisinopril, the pharmacy sends a claim to your PBM. The PBM doesn’t pay the pharmacy the same amount it charges your insurer. That’s the first trick. PBMs use a benchmark called the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) to set reimbursement rates. But here’s the catch: they often reimburse pharmacies less than what they charge your insurance plan. The difference? That’s called spread pricing. In 2024, this practice generated $15.2 billion in hidden revenue for PBMs, with 68% of it coming from generic drugs. For example, your insurer might be billed $12 for a 30-day supply of generic atorvastatin. The pharmacy, meanwhile, gets reimbursed $7. The PBM pockets the $5 difference. You still pay your $10 copay. So you pay $10, the insurer pays $12, the pharmacy gets $7, and the PBM keeps $5. No one tells you that’s happening.Why Your Copay Is Higher Than the Cash Price

This system creates bizarre outcomes. A 2024 Consumer Reports survey found that 42% of insured adults paid more out of pocket for a generic drug through insurance than they would have if they’d paid cash. One Reddit user shared they paid $45 for a generic cancer drug through insurance-while the same drug cost $4 if paid upfront at the pharmacy. Why? Because insurers and PBMs often structure copays as fixed amounts ($5, $10, $20) regardless of the actual drug cost. If the PBM sets the reimbursement rate at $3 but charges the insurer $25, your $10 copay might still leave you paying more than the true market price. Meanwhile, someone walking in without insurance pays the cash price-often the lowest price available-because pharmacies are free to offer discounts to cash customers. Independent pharmacists report seeing this daily. They’ll hand you a prescription and say, “You can pay $6.50 cash, or use your insurance and pay $38.” Most patients don’t know they have a choice.

The Hidden Costs for Pharmacies

Pharmacies don’t get off easy either. They’re stuck navigating hundreds of different PBM contracts, each with its own reimbursement rules, formulary lists, and clawback policies. A clawback happens when a PBM later decides a pharmacy was overpaid and demands money back-even after the patient has already left the store. According to the National Community Pharmacists Association, 63% of independent pharmacies have faced clawbacks. To manage this chaos, many pharmacies spend $12,500 on billing software and hire PBM specialists at $100,000 a year just to decode the contracts. Some spend 200-300 hours a year trying to understand how much they’ll get paid for each generic drug. Between 2018 and 2023, 11,300 independent pharmacies closed. Many couldn’t survive the shrinking reimbursement rates and administrative burden.Why This System Still Exists

You might wonder: if it’s so broken, why hasn’t it changed? The answer is money. PBMs argue they save money by negotiating bulk discounts. And they do-just not always for you. The real savings often go to insurers, who keep premiums low by shifting costs to copays and deductibles. Drugmakers also benefit. PBMs demand rebates based on the list price of drugs. So the higher the list price, the bigger the rebate-and the more money PBMs and insurers make. That creates a perverse incentive: drugmakers raise list prices to secure better deals, even if it doesn’t change what patients actually pay. A 2023 JAMA commentary by Dr. Joseph Dieleman put it bluntly: “The current PBM system creates perverse incentives where higher list prices generate larger rebates, ultimately increasing patient cost-sharing burdens.”

What’s Changing-and What’s Not

Pressure is building. In September 2024, the Biden administration issued an executive order banning spread pricing in federal health programs, with the rule taking effect in January 2026. Forty-two states have passed or are considering laws requiring PBM transparency. The 2025 Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program will expand to 20 drugs, forcing manufacturers to negotiate prices directly with CMS. Legislators are also pushing the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2025, which would require PBMs to pass all rebates directly to insurers-cutting out the middleman’s profit. McKinsey & Company predicts spread pricing revenue could drop 25% by 2027. But don’t expect a quick fix. The pharmaceutical industry argues that without rebates and complex negotiations, innovation would suffer. They claim the system funds new drug development. Critics counter that most innovation comes from public research, and the current model just enriches middlemen.What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t have to wait for policy changes to save money on generics. Here’s what works:- Always ask the pharmacist: “What’s the cash price?”

- Use apps like GoodRx, SingleCare, or RxSaver to compare prices across nearby pharmacies.

- If your copay is higher than the cash price, pay cash. Your insurance won’t know the difference.

- Ask your doctor to prescribe drugs on your plan’s formulary-but don’t assume formulary = cheap.

- Call your insurer and ask: “What’s the NADAC for this drug? What’s my pharmacy’s reimbursement rate?” You might be surprised they can’t answer.

Why This Matters

Generics make up 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. But they account for only 23% of total drug spending-because the system is designed to make you pay more, even for cheap medicine. The gap between what insurers are billed, what pharmacies get paid, and what you’re charged isn’t a glitch. It’s the business model. The real cost isn’t just financial. It’s trust. When patients are forced to choose between paying $40 for a pill they thought was covered-or walking out empty-handed-they lose faith in the whole system. And when pharmacies are squeezed out of business, access to care shrinks, especially in rural areas. The next time you fill a generic prescription, remember: the price on your receipt isn’t the real price. It’s just one number in a long chain of hidden deals.Why do I pay more for a generic drug with insurance than without?

Because your insurer and PBM set a fixed copay based on a negotiated reimbursement rate that’s often lower than what they charge the insurer. The difference-called spread pricing-goes to the PBM as profit. Meanwhile, pharmacies can offer lower cash prices to customers who pay upfront, since they’re not bound by PBM contracts. So even though you have insurance, you’re paying more than someone paying cash.

What is spread pricing?

Spread pricing is when a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) charges your insurer a higher price for a drug than it pays the pharmacy to dispense it. The difference is kept by the PBM as profit. For example, if your insurer is billed $15 for a generic drug but the pharmacy is only paid $8, the $7 spread goes to the PBM. This practice is hidden from patients and was recently banned in federal programs starting in 2026.

Do PBMs actually save money for patients?

PBMs claim they lower costs by negotiating bulk discounts, but the savings rarely reach patients. Instead, rebates and spread pricing often enrich PBMs and insurers. A 2024 Stanford study found that while gross discounts from drugmakers can reach 80%, patients still pay high copays because those discounts don’t translate into lower out-of-pocket costs. The real savings go to insurers who keep premiums low by shifting costs to copays and deductibles.

Why can’t pharmacists tell me the cash price?

Most PBM contracts include gag clauses that legally prevent pharmacists from telling you the cash price is lower than your insurance copay. These clauses were common in 92% of PBM contracts as of 2024. While some states have banned them, they’re still in place in many areas. Even if a pharmacist wants to help, they could face penalties from the PBM.

What’s being done to fix this system?

In January 2026, spread pricing will be banned in federal programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Forty-two states are passing PBM transparency laws requiring disclosure of pricing practices. The Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2025 would force PBMs to pass all rebates to insurers. The Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program is also expanding, which could pressure private insurers to follow suit. But change is slow, and PBMs still control most of the market.

Solomon Ahonsi February 3, 2026

This whole system is a scam. I paid $38 for metformin with insurance last month. Cash price? $5.50. No one tells you this. Pharmacies can't even say anything because of those gag clauses. PBMs are just glorified thieves with fancy offices and MBA degrees.