When you pick up a generic pill, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. That’s the whole point. But what if the ad on TV, the billboard, or the website you clicked on made you think it was better-or worse-than it really is? That’s not just misleading. It’s illegal. And the consequences are serious.

What Counts as False Advertising in Generic Drugs?

False advertising in generic pharmaceuticals isn’t about lying outright. It’s about what’s implied. Saying a generic drug is "just as good" is fine. Saying it’s "FDA Approved" when it’s only been cleared? That’s a problem. Claiming a generic is "safer" or "more effective" without head-to-head clinical trials? That’s a violation. Even using visuals that make your pill look identical to the brand-name version-same shape, same color, same logo-can confuse patients and cross the line. The FDA requires generics to prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That means the body absorbs the active ingredient at nearly the same rate and level-within 80% to 125% of the original. But bioequivalence doesn’t mean identical in every way. Fillers, coatings, and inactive ingredients can differ. And that’s okay-unless the ad suggests those differences don’t matter when they actually do.The Laws That Keep Generics Honest

Three main laws are used to crack down on false claims in generic drug ads:- The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) gives the FDA authority over drug labeling and advertising. It says ads must present a "fair balance" between benefits and risks. No cherry-picking.

- The Lanham Act lets competitors sue each other for deceptive marketing. If a generic company claims its drug is "therapeutically equivalent" without FDA approval for that specific use, the brand-name maker can take them to court. And they have-multiple times.

- State consumer protection laws like New York’s General Business Law § 349 and California’s Unfair Competition Law let patients and attorneys go after misleading ads too. In New York, courts can award triple damages-up to $1,000 per violation.

What You Can’t Say (And What You Can)

There’s a tight line between legal and illegal in generic advertising. Here’s what’s allowed and what’s not:| Allowed | Prohibited |

|---|---|

| "This is a generic version of [Brand Name]" | "This generic is safer than the brand-name drug" |

| "Saves you up to 80%" (if substantiated with real pricing data) | "FDA Approved" (unless the specific generic has received FDA approval for that use) |

| "Bioequivalent to [Brand Name]" | "Identical to [Brand Name]" (unless proven for all components) |

| "Approved for same uses as [Brand Name]" | "No side effects" or "No risk" |

| "Lower cost alternative" | "Health alert: Avoid generics" (fear-based messaging) |

Who Gets Hurt When Ads Are False?

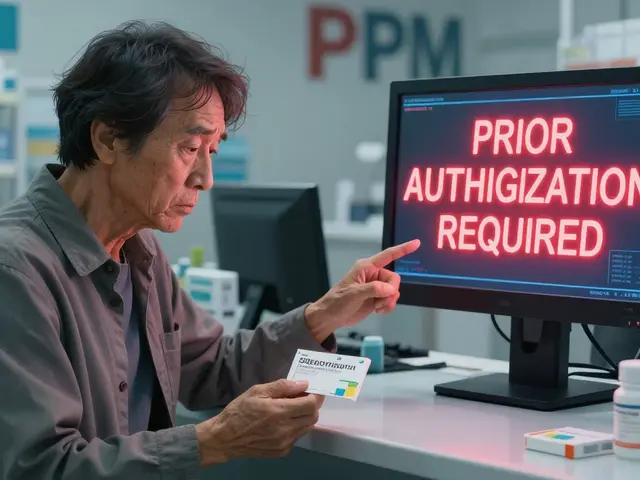

Patients pay the biggest price. A 2024 FDA analysis of over 1,200 patient complaints found that 32% of people stopped taking their medication because they believed misleading ads claiming generics were unsafe. Many ended up in the ER with uncontrolled conditions-high blood pressure, seizures, or thyroid crashes. On Reddit, users shared stories of being told by pharmacists they couldn’t fill a generic because "the doctor said no"-even though the doctor never said that. The misinformation came from a YouTube ad that showed a generic pill next to a red warning sign. Doctors get caught in the middle. The American Medical Association found that 67% of physicians say patients now ask for brand-name drugs because of ads, even when the generic is cheaper and equally effective. That strains the system and drives up costs. And let’s not forget the companies. In 2025, the FDA issued over 100 cease-and-desist letters to generic manufacturers for misleading comparisons. One company used a jingle that sounded identical to a brand-name ad. Another used the same blue-and-white color scheme as the original. Both were forced to pull their campaigns-and pay fines.The Hidden Costs of Noncompliance

It’s not just about fines. The real cost is reputation. Once a company is linked to false advertising, doctors stop prescribing their products. Pharmacies stop stocking them. Patients avoid them. For major manufacturers, compliance teams spend $2 million a year just vetting ads. That’s 15 to 25 people-lawyers, medical writers, regulatory specialists-reviewing every word, every image, every claim. Smaller companies? They often can’t afford that. And that’s why compliance rates drop to 47% among smaller generic makers, according to FDA data from October 2025. The penalties add up fast:- Up to $10,000 per violation under New York law

- Triple damages under the Lanham Act

- Forced ad removal and public correction notices

- Loss of FDA approval for future products

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The biggest shift? The FDA is closing the "adequate provision" loophole. Since 1997, TV and radio ads could say, "For full risk information, visit [website]." That meant patients never heard the real risks during the ad. Starting in 2026, all broadcast and digital ads must include complete risk disclosures-right in the message. No links. No footnotes. No fine print. Just clear, visible, audible warnings. The FDA is also pushing for more coordination with the FTC. New draft legislation, H.R. 4582, would standardize risk disclosure rules across all media. That means no more loopholes. And enforcement? It’s only getting stricter. Evaluate Pharma predicts a 35% annual increase in enforcement actions through 2027. Generic manufacturers are now the #1 target-not because they’re more likely to cheat, but because their ads have the biggest impact on public health and costs.How to Stay Compliant

If you’re a manufacturer, marketer, or pharmacist, here’s how to avoid trouble:- Always use the exact FDA-approved language for bioequivalence claims.

- Never imply superiority unless you have head-to-head clinical trial data.

- Use the phrase "This is a generic drug" clearly and early in every ad.

- Disclose all major side effects in the ad itself-no "visit our website" tricks.

- Train your team. The learning curve for compliance officers is 18 months. Don’t guess.

- Check state laws. Florida bans government logos in ads. California requires stricter proof for cost claims.

Can a generic drug be called "FDA Approved"?

No-not unless the specific generic product has received FDA approval for that exact use. Many companies say "FDA Approved" to imply the brand-name’s approval applies to them. That’s false. Only the brand-name drug gets an NDA (New Drug Application). Generics get an ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application). The correct phrasing is "This generic is approved by the FDA" or "FDA-approved generic version of [Brand Name]."

Are generics really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes-if they meet FDA bioequivalence standards. The FDA requires generics to deliver the same active ingredient at the same rate and level as the brand-name drug, within a tight 80-125% range. For most drugs, that’s functionally identical. For narrow therapeutic index drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin, the FDA has extra monitoring, but still confirms generics are safe and effective when properly manufactured. The myth that generics are inferior comes from misleading ads, not science.

Can I sue a company for false generic drug advertising?

Yes. Under the Lanham Act, competitors can sue. Under state consumer protection laws like New York’s § 349, patients can sue too. You don’t need to be injured to file-just show you were misled. Many class-action lawsuits have been filed against companies using fear-based language like "dangerous generics" or "health alert" without FDA backing. Courts have awarded damages in the millions.

Why do some doctors refuse to prescribe generics?

Some do because of patient pressure from misleading ads. Others worry about narrow therapeutic index drugs, where even small absorption differences matter. But the FDA has approved thousands of generic substitutions for these drugs. Doctors who refuse without medical reason may be responding to misinformation, not science. The American Medical Association recommends generics unless there’s a documented clinical issue.

What should I look for in a legitimate generic drug ad?

A legal ad will clearly state: "This is a generic version of [Brand Name]," name the active ingredient, list major risks in the ad itself (not just online), and avoid claims of superiority or safety. It won’t use the brand’s logo, color scheme, or jingle. It won’t say "FDA Approved" without context. If it sounds too good-or too scary-to be true, it probably is.

dean du plessis December 28, 2025

Generics work fine unless you're one of those people who thinks the color of the pill changes how it works. I've been on generic levothyroxine for five years and my TSH is perfect. No drama, no crashes, just a cheaper pill that does the job.

Satyakki Bhattacharjee December 30, 2025

People don't understand that medicine isn't a brand. It's science. But ads make it seem like generics are some kind of cheap knockoff. It's not about money, it's about trust. And when companies lie to make a buck, they're not just breaking laws-they're breaking the bond between patient and healer.

Nicola George December 31, 2025

Oh so now the FDA is the pharmacy police? Next they'll ban blue pills because they look too much like the brand. At least the ads are honest about one thing-people will believe anything if it’s scary enough.

Kylie Robson January 1, 2026

Let’s clarify the regulatory architecture here: the ANDA pathway doesn’t equate to diminished efficacy-it’s a bioequivalence paradigm anchored in pharmacokinetic parameters, specifically Cmax and AUC within the 80–125% confidence interval. The FDA’s 2025 guidance explicitly prohibits inferential claims of superiority absent head-to-head RCTs. Misuse of the term ‘FDA Approved’ without ANDA context constitutes a 21 CFR § 202.1(e)(6) violation.

Kishor Raibole January 3, 2026

It is a matter of profound moral concern that commercial interests, driven by profit motives, seek to manipulate public perception through deceptive advertising. The pharmaceutical industry, in its pursuit of market dominance, has eroded the very foundation of informed consent. When a patient is misled into believing that a life-sustaining medication is inferior, the ethical breach is not merely legal-it is existential.

Monika Naumann January 4, 2026

India produces 40% of the world’s generics. We have the most rigorous testing protocols. If American companies can’t compete without fearmongering, that’s their problem. The real danger isn’t the pill-it’s the fear they sell.

Elizabeth Ganak January 5, 2026

i used to be scared of generics too until my doctor switched me and i saved $120 a month. my anxiety didn’t get worse, my sleep didn’t suck, and my bank account didn’t cry. why are we still talking about this?

Gerald Tardif January 7, 2026

Some of these ads are straight-up scary-like they’re selling horror movies instead of medicine. I’ve seen a guy in a lab coat point at a generic pill like it’s a bomb. That’s not marketing, that’s psychological warfare. And it’s working. People are skipping doses because they’re terrified of a pill that’s been proven safe.

Liz MENDOZA January 7, 2026

I’m a pharmacist and I see this every day. Patients come in panicked because of a YouTube ad. They’ve been told generics are ‘unsafe’ or ‘not real medicine.’ I spend 10 minutes explaining bioequivalence, showing them the FDA’s data, and then they just nod and leave. It’s heartbreaking. We need better public education, not just enforcement.

Will Neitzer January 7, 2026

It is imperative to recognize that the systemic misrepresentation of generic pharmaceuticals constitutes not merely a regulatory infraction, but a public health emergency of significant magnitude. The deliberate propagation of misinformation, particularly through emotionally manipulative media, directly undermines the integrity of evidence-based medicine. The FDA’s 2025 enforcement initiative represents a necessary and overdue corrective mechanism, aligned with the ethical obligations of the medical profession to prioritize patient welfare over commercial expediency. Compliance is not optional-it is foundational to the social contract between provider, patient, and pharmaceutical entity.