What Specific IgE Testing Actually Measures

Specific IgE testing is a blood test that finds out if your body has made antibodies called immunoglobulin E (IgE) in response to particular allergens. These antibodies are your immune system’s overreaction to harmless substances like pollen, peanuts, or cat dander. When you’re exposed to one of these triggers, your body may produce IgE antibodies that stick to the allergen, setting off symptoms like sneezing, hives, or even anaphylaxis.

This test doesn’t measure your total IgE levels - it zeroes in on IgE that’s specific to one allergen at a time. For example, if you’re allergic to birch pollen, the test will detect only the IgE antibodies that react to birch pollen proteins, not to ragweed or dust mites. The results come back in kUA/L units, with anything below 0.35 kUA/L considered normal. A number above that doesn’t automatically mean you’re allergic - it just means your immune system has seen that allergen before and made some antibodies.

How the Test Has Changed Since the 1970s

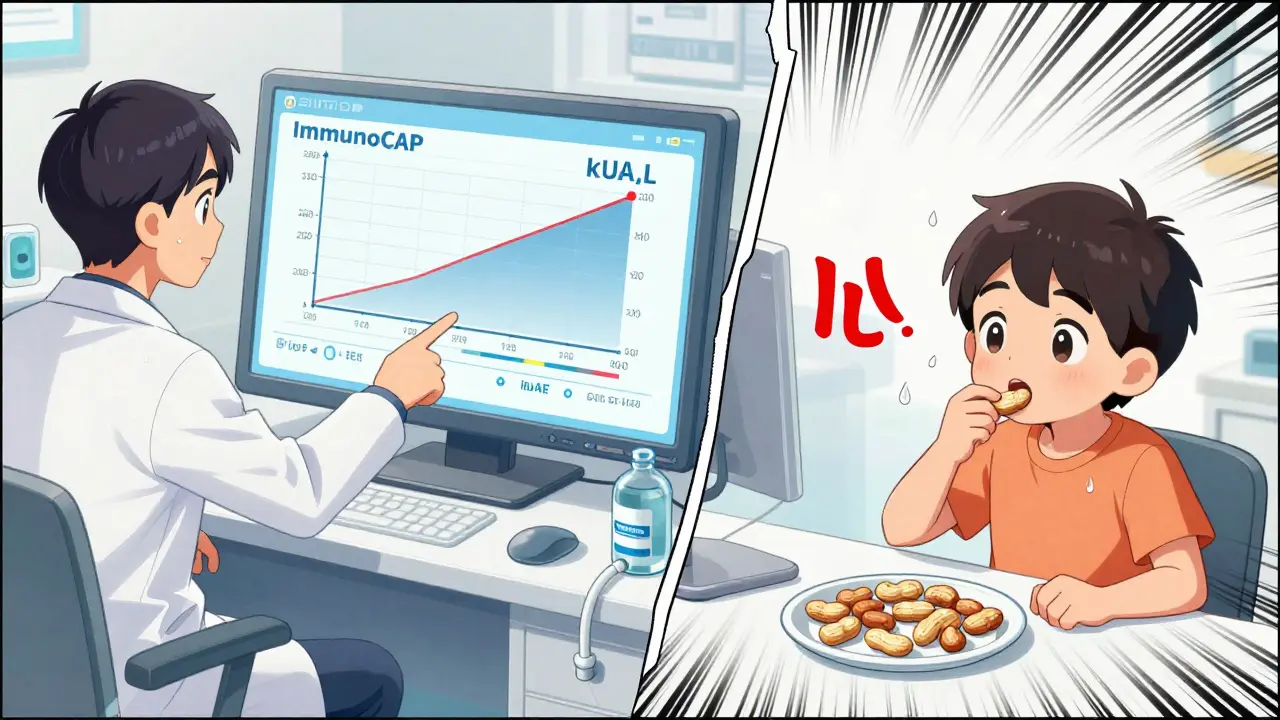

Back in 1972, the first version of this test was called RAST - radioallergosorbent test. It used paper disks coated with allergens and could only say yes or no: was there IgE present or not? Today’s tests are completely different. The gold standard now is ImmunoCAP, a method that uses a tiny capsule filled with a flexible polymer to capture IgE antibodies from your blood. This lets labs measure the exact amount of IgE, not just detect its presence.

Modern platforms like ImmunoCAP can detect levels as low as 0.1 kUA/L, with accuracy better than 95% in repeat tests. In the UK, 85% of labs now use ImmunoCAP or similar systems like HyCor’s HYTEC 288. These aren’t just fancier versions of old tech - they’re more precise, faster, and far less likely to give false results. And because they’re quantitative, doctors can now track changes over time. If your peanut IgE drops from 12 kUA/L to 3 kUA/L after avoiding peanuts for a year, that’s meaningful information.

When Doctors Order This Test - And When They Don’t

Not everyone with allergies needs a blood test. In fact, skin prick testing is still the first choice for most people because it’s cheaper, faster, and shows real-time reactions in your skin. But there are clear reasons to choose blood testing instead. If you have severe eczema covering more than 40% of your body, skin tests won’t work well - the skin is too damaged. If you’re taking antihistamines, antidepressants, or other meds that block allergic reactions, you can’t stop them for the 3-5 days needed before a skin test. That’s why 27% of pediatric patients in the U.S. get blood tests instead.

But here’s the big problem: too many people get tested when they shouldn’t. Studies show that 22% of IgE tests ordered in primary care are unnecessary. Why? Because doctors sometimes order broad panels - testing for 20 or more allergens at once. That’s a recipe for false positives. The more tests you run, the more likely you are to get a random positive result that means nothing. A 2025 UK guideline says no more than 12 specific IgE tests should be ordered without clear clinical justification. And food mix tests? Don’t bother. They’re wrong more than 30% of the time.

Interpreting Your Results: Numbers Don’t Tell the Whole Story

A result of 0.5 kUA/L for milk doesn’t mean the same thing for everyone. If your total IgE is only 1 kUA/L, then 0.5 kUA/L is half your total allergy antibody level - that’s significant. But if your total IgE is 100 kUA/L, then 0.5 kUA/L is just a tiny fraction. That’s why labs now automatically check total IgE when a specific IgE comes back positive. It helps doctors put the number in context.

Also, the higher the specific IgE number, the more likely you are to have a real allergy. For peanut allergy, a result of 0.35 kUA/L means you have about a 50% chance of reacting if you eat peanuts. But at 15 kUA/L, that chance jumps to 95%. That’s why doctors don’t just look at whether the number is above 0.35 - they look at how far above it is. A weak positive (0.35-0.70 kUA/L) often needs more investigation: maybe a food challenge, maybe a history of reactions, maybe component testing.

Component-Resolved Diagnostics: The Next Step

Some allergens are made up of many different proteins. For example, cashew nuts contain over 20 proteins. Some of these proteins cause real allergic reactions. Others are similar to proteins in birch pollen - so if you’re allergic to birch, you might test positive for cashew, but you can eat cashew just fine. This is called cross-reactivity.

Component-resolved diagnostics (CRD) test for IgE to individual proteins, not whole allergens. For cashew, it can distinguish between Ana o 3 (a protein linked to severe reactions) and other proteins that cause only mild or no symptoms. This improves accuracy from 70% to 92%. It’s not used everywhere yet - only in specialist allergy centers - but it’s becoming more common for people with confusing test results or unclear histories.

What the Test Can’t Do

Specific IgE testing won’t tell you how bad your reaction will be. A high number doesn’t mean you’ll go into anaphylaxis - it just means you’re sensitized. Some people with very high IgE levels can eat the food without problems. Others with low levels react badly. That’s why your history matters more than the number.

This test also won’t help if you have non-IgE allergies. Many food intolerances - like lactose intolerance or gluten sensitivity - don’t involve IgE at all. If you get bloated after dairy but don’t break out in hives or swell up, this test won’t help. And it’s not for diagnosing chronic conditions like eczema or asthma unless there’s a clear link to a specific allergen.

How the Test Is Done - And How Long It Takes

Getting the test is simple. A nurse draws about 2 mL of blood from your arm, usually into a yellow-top tube with a gel separator. No fasting or special prep is needed. You can eat, drink, and take your regular meds. The sample gets sent to the lab, and most results come back in 3 business days. Some rare allergens - like certain insect venoms or tropical foods - need to be sent to specialist labs like Sheffield, which can add another week.

It’s not an emergency test. Ninety-eight percent of these tests are ordered for ongoing management, not acute reactions. If you just had a reaction, you don’t wait for the blood test - you get treated right away. The test comes later to figure out what caused it.

Why Skin Testing Is Still Preferred - But Blood Has Its Place

Skin prick testing is faster, cheaper, and more sensitive for common allergens like dust mites and pollen. It shows an immediate reaction - a red, itchy bump - which proves the allergen is active in your body. Blood tests only show that IgE antibodies are floating around. They don’t prove the allergen will cause symptoms.

But blood tests have one big advantage: they’re not affected by skin condition or medications. If you’re on antihistamines, you can’t do skin testing. If you have eczema covering your back and arms, skin testing is impossible. Blood tests work regardless. For kids with severe eczema or adults on multiple medications, blood testing is the only option.

What Happens After the Results?

If your test comes back positive, your doctor won’t just say, “Avoid this.” They’ll look at your history. Did you eat peanuts last year and get hives? Then a positive test means something. Did you never eat shellfish but test positive for shrimp? That might be cross-reactivity - and you’re probably fine.

Positive results can lead to allergy shots (immunotherapy), especially for pollen or dust mites. Or they might lead to an oral food challenge, where you eat small amounts of the food under medical supervision to see if you react. Sometimes, the test is used to confirm you’ve outgrown an allergy - like milk or egg - by showing IgE levels have dropped over time.

Common Mistakes People Make

- Testing without symptoms: If you’ve never had a reaction to cats, don’t test for cat IgE just because you’re thinking about getting one.

- Believing a low number means you’re safe: A result of 0.4 kUA/L might still be meaningful if you’ve had a reaction before.

- Ignoring total IgE: A weak positive means nothing without knowing your overall IgE level.

- Ordering too many tests: Testing for 20 foods at once gives you false positives. Stick to what’s relevant.

- Thinking the test is urgent: It’s not. You’ll wait days for results. If you’re having a reaction now, go to the ER.

What’s Next for Allergy Testing?

One new tool is the ImmunoSolid Phase Allergen Chip (ISAC), which can test for 112 different allergen components from just 20 microliters of blood. That’s a lot of data from one tiny sample. But interpreting it? That’s complex. It requires an allergist with special training. Right now, it’s only used in specialist centers in the UK and Europe.

What’s clear is that testing is becoming smarter. We’re moving away from broad panels and toward targeted, personalized testing based on your history. The goal isn’t to find every possible allergen - it’s to find the ones that matter to you.

Lynsey Tyson December 19, 2025

I got my IgE results last month and honestly? I was terrified. Turns out my 0.8 kUA/L for peanuts was just cross-reactivity with birch pollen. I’ve eaten peanut butter since I was 5. No issues. So much drama over a number that didn’t mean what I thought it did.

Dominic Suyo December 20, 2025

This is why medicine is a circus. They spend millions on ImmunoCAP, then hand you a 12-panel test like it’s a bingo card. I once saw a guy get tested for 17 foods because he "felt weird" after eating a burrito. He’s now on a 10-food elimination diet. All because someone thought more tests = better care. Sad.

Kelly Mulder December 21, 2025

The notion that a 0.35 kUA/L threshold is somehow diagnostic is laughably outdated. In clinical immunology, we treat the patient-not the algorithm. The reliance on arbitrary cutoffs without contextualizing total IgE or component profiles is not just poor medicine-it’s negligent. I have reviewed over 300 such cases in the last two years. The majority are misinterpreted.

anthony funes gomez December 22, 2025

The IgE paradigm is fundamentally flawed-it conflates sensitization with clinical allergy. The immune system is not a binary switch. It’s a dynamic, context-dependent network. A positive IgE result is merely a molecular footprint-not a prophecy. Component-resolved diagnostics offer a pathway out of this reductive trap-but only if clinicians are trained to read beyond the spreadsheet. We need epistemological humility in allergy medicine.

Mark Able December 22, 2025

I had a 15 kUA/L result for shellfish and ate shrimp at a restaurant last week. No reaction. Zero. Not even a tingle. So what does that number even mean? I think doctors just like to scare people into avoiding things. I’m just gonna keep eating what I want. My body knows better than a lab report.

Dorine Anthony December 23, 2025

I’m so glad someone wrote this. My kid had eczema so bad they couldn’t do skin tests. Blood test came back positive for milk, egg, soy. We avoided everything for 6 months. Turned out he was fine. Just had a weird immune blip. The doctor said the numbers were "low but present" and we should wait. So we waited. And he outgrew it. Don’t panic over numbers.

James Stearns December 25, 2025

The proliferation of unvalidated, broad-panel IgE testing constitutes a systemic failure of clinical governance. It is not merely inefficient-it is ethically indefensible. The economic incentives driving these tests are transparent. The consequences? Misdiagnosis, unnecessary dietary restriction, and iatrogenic anxiety. Regulatory bodies must intervene. This is not science. It is commodified fear.

Edington Renwick December 25, 2025

I saw a guy on Reddit who tested positive for 14 foods. He’s now on a liquid diet. He thinks his dog is poisoning him. He’s not wrong. But it’s not the IgE. It’s the panic. I’ve seen this movie before. It ends with a therapist, a food journal, and a lot of tears. Don’t be that guy.

Janelle Moore December 25, 2025

Did you know the FDA doesn’t regulate these tests? Labs just make up the cutoffs. And the companies that make ImmunoCAP? They pay doctors to order them. I’ve got a spreadsheet. I’ve got emails. I’ve got the whole picture. You think this is science? It’s a billion-dollar scam. They’re selling you fear. And they’re getting rich off your anxiety.

Monte Pareek December 27, 2025

Let me break this down for you. If you’ve never had a reaction, don’t test. If you’ve had a reaction, your history matters more than the number. If you’re on meds or have eczema, blood test is your friend. If you’re getting 20 tests at once? Stop. Ask your doc: what’s the question? What’s the plan? If they can’t answer, get a second opinion. This isn’t rocket science-it’s common sense. But it’s getting buried under junk science.

Emily P December 28, 2025

I’m curious-how often do people get false negatives? Like, if you’re allergic but the test says negative? Is that common? I’ve heard of cases where someone reacts badly but the IgE is undetectable. Does component testing help with that? Or is that just non-IgE?

Vicki Belcher December 29, 2025

This post saved my life 🙏 I had no idea total IgE mattered. My doctor just said "avoid peanuts" and I was terrified. Now I know my 0.6 kUA/L is only 0.5% of my total IgE. I’m not avoiding peanut butter anymore 😊 I even ate a PB&J last week and didn’t die. Thank you for explaining it so clearly!