Every time you pick up a generic prescription, there’s a hidden system at work-shaped by federal laws, state regulations, and corporate contracts-that decides how much the pharmacy gets paid and how much you pay at the counter. It’s not just about the price of the pill. It’s about who controls the money, how the rules change from state to state, and why your $4 generic sometimes costs $12.

How Generic Drugs Are Paid For

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they account for only 23% of total drug spending. That’s the whole point: they’re cheaper. But how much cheaper? And who decides?

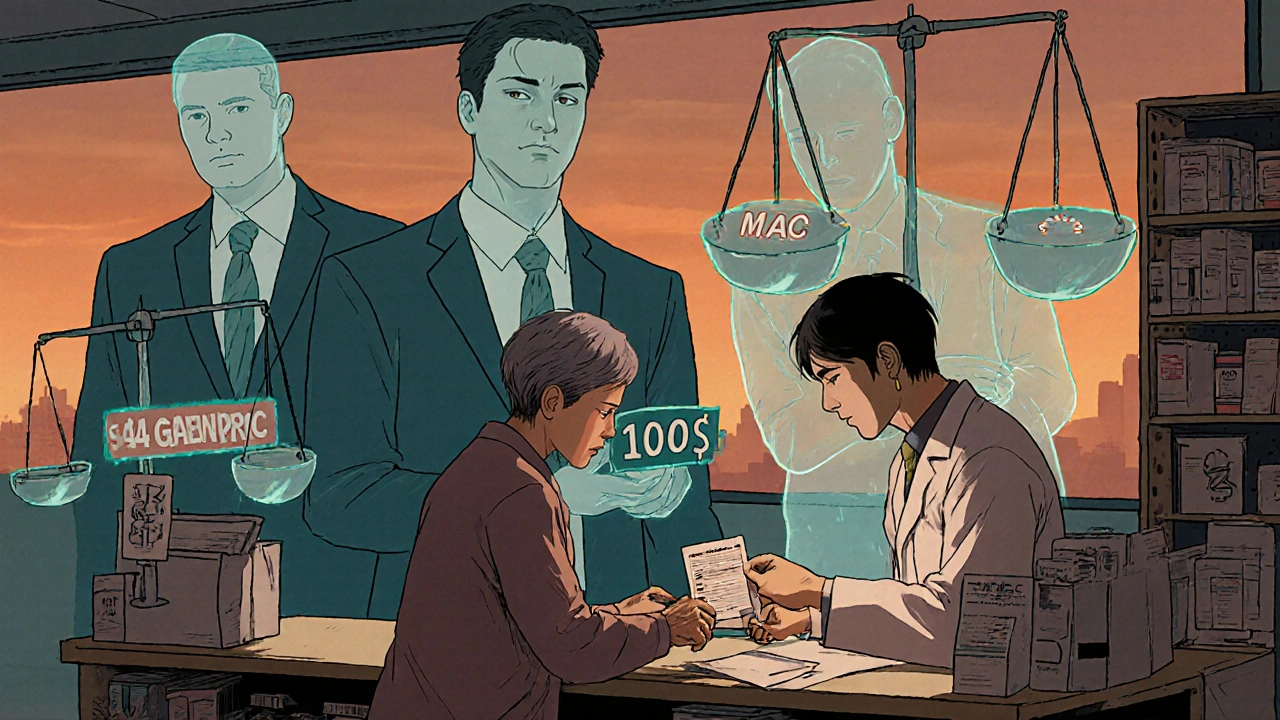

Pharmacies don’t get paid the same way for every drug. For generics, reimbursement usually follows one of two models: Average Wholesale Price (AWP) or Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). AWP is an outdated list price that used to be the standard, but it’s rarely used anymore for generics because it doesn’t reflect real costs. MAC is the system you’ll find in most Medicare Part D and Medicaid plans today. It sets a fixed maximum amount a pharmacy can be reimbursed for each generic drug-say, $2.50 for a 30-day supply of lisinopril. If the pharmacy paid $3.20 to buy it, they eat the $0.70 loss. If they paid $2.00, they keep the $0.50 profit.

That’s where things get messy. MAC lists are updated by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), not pharmacists. And those updates don’t always match what pharmacies actually pay. In 2023, the National Community Pharmacists Association found that the average reimbursement margin for generics was just 1.4%. That’s down from 3.2% in 2018. For many small pharmacies, that’s not enough to cover rent, staff, or even the cost of running the cash register.

The Role of Medicare Part D and Medicaid

Medicare Part D covers 50.5 million people, and it’s where most of the rules for generic reimbursement are set. Part D plans use formularies-lists of approved drugs-to control costs. Generics are usually on the lowest tier, meaning lower copays. But here’s the catch: not all generics are treated equally. Some plans put certain generics on a higher tier if they’re not on the preferred list. That means a patient might pay $10 for one generic version of metformin and $4 for another-even though they’re the same drug.

Medicaid, which covers 85 million Americans, uses Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs). Each state decides which generics are preferred. If a doctor prescribes a non-preferred generic, the pharmacy might need prior authorization. That means delays, paperwork, and sometimes patients skipping their meds because the process is too complicated.

Both programs rely on rebate systems. Drug manufacturers pay rebates to PBMs and states to get their drugs on preferred lists. But here’s the irony: those rebates often lead manufacturers to raise list prices. The higher the list price, the bigger the rebate-and the more money PBMs make. Meanwhile, pharmacies get paid based on the lower MAC rate. The patient pays the copay, the PBM takes the rebate, and the pharmacy is left with crumbs.

How PBMs Shape the Game

Three companies-CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRX-handle over 80% of all prescription claims in the U.S. These are pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs. They don’t dispense drugs. They don’t own pharmacies. But they control who gets paid what.

PBMs negotiate with drug makers, set MAC lists, and collect “spread pricing”-the difference between what the insurer pays and what the pharmacy gets paid. For example: the insurer pays $10 for a generic. The pharmacy is reimbursed $6. The PBM keeps $4. That’s spread pricing. Until 2018, PBMs could legally prevent pharmacists from telling patients they could pay less out-of-pocket by skipping insurance entirely. These were called “gag clauses.” Now banned, but the damage is done. Many patients still don’t know they can ask the pharmacist to check cash prices.

Independent pharmacies are especially vulnerable. They don’t have the negotiating power of big chains like Walgreens or CVS. If a PBM cuts their reimbursement rate, they can’t afford to lose the contract. So they take the hit. In 2023, the average generic drug profit margin for independent pharmacies was 1.4%. That’s less than the cost of a cup of coffee per prescription.

State Laws Are Changing the Rules

While federal laws set the stage, states are now stepping in to fix the cracks. As of 2023, 44 states passed laws regulating how PBMs reimburse pharmacies for generics. Some require PBMs to disclose MAC pricing. Others ban spread pricing entirely. A few, like California and New York, now require PBMs to pay pharmacies the actual acquisition cost of the drug-not an arbitrary MAC rate.

These laws are starting to make a difference. In states with transparency rules, pharmacies report better cash flow. Patients are more likely to fill prescriptions when they know what they’re paying. But enforcement is uneven. Many small pharmacies still don’t know their rights. And PBMs often fight these laws in court.

The $2 Drug List: A New Model

In 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched a new voluntary model: the Medicare $2 Drug List. It’s simple: pick about 100 to 150 generic drugs that are clinically important, widely used, and already low-cost. Then, make them $2 for every Medicare Part D beneficiary-no deductible, no copay, no surprise.

Drugs on the list include metformin, levothyroxine, lisinopril, and atorvastatin. These are the same drugs that make up the bulk of prescriptions for seniors. The goal? Reduce out-of-pocket costs, improve adherence, and cut administrative clutter. Early projections suggest this could save Medicare $1.2 billion annually.

But it’s not perfect. PBMs aren’t required to participate. And drug manufacturers can still push higher-priced alternatives. Still, it’s the first time the federal government has directly capped generic drug prices for seniors. If it works, it could become a national standard.

What This Means for You

If you’re on Medicare or Medicaid, your out-of-pocket cost for a generic drug depends on your plan’s formulary, your state’s laws, and whether your pharmacy is in-network. You might pay $4.50. You might pay $15. It’s not random-it’s calculated.

Here’s what you can do:

- Always ask your pharmacist: “Can I pay cash instead of using insurance?” Sometimes the cash price is lower than your copay.

- Check if your plan has a preferred generic list. If your drug isn’t on it, ask your doctor for an alternative.

- If you’re on Medicare, look up your plan’s formulary online. Look for the tier your generic is on. Higher tier = higher cost.

- Use tools like GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices across pharmacies in your area.

And if you’re a pharmacy owner? You’re fighting a system designed to squeeze your margins. Know your state’s laws. Demand transparency from your PBM. And don’t be afraid to speak up.

What’s Next?

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped insulin at $35 a month and will cap total out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 for Medicare Part D in 2025. That’s huge. But it doesn’t fix the underlying problem: reimbursement models that don’t reflect real costs.

Experts predict generic drug prices will keep falling 5-7% a year through 2027. But if pharmacies keep getting paid less than it costs to stock and dispense them, more will close. That’s not savings-that’s access loss.

The future may lie in value-based payments-where pharmacies are rewarded for keeping patients healthy, not just for filling bottles. But that’s years away. Right now, the system is still built on outdated formulas, hidden fees, and a lack of transparency.

Generics are the cheapest way to treat chronic conditions. But they’re only cheap if the system works for everyone-not just the middlemen.

Skye Hamilton November 28, 2025

so like… the system is literally designed to make pharmacies lose money on the cheapest meds? that’s not a bug, that’s the whole damn feature

Craig Hartel November 30, 2025

my grandma takes lisinopril and metformin every day. she never asks about pricing because she trusts the pharmacist. turns out she’s been overpaying for years. i’m gonna show her how to use GoodRx tomorrow. small win, but it matters

Hannah Magera December 2, 2025

if you’re on meds long-term, always ask the pharmacist about cash prices. i saved $28 a month just by switching from insurance to cash for my thyroid pill. no one tells you this. it’s not rocket science, just hidden

Brandon Trevino December 3, 2025

the MAC system is a textbook example of regulatory capture. PBMs extract surplus value by manipulating acquisition cost data while pharmacies bear the operational burden. this is not market efficiency-it’s rent-seeking disguised as cost containment

Nicola Mari December 5, 2025

you people are naive. this isn’t about drugs-it’s about control. the same entities that run your insurance also run your pharmacy benefits. they want you dependent. they want you silent. don’t be fooled by $2 lists-they’re just PR

Denise Wiley December 6, 2025

my local pharmacy shut down last year. the owner cried when he told us he couldn’t afford to keep running it. he was making less than $1 profit per generic script. i still miss him. he knew everyone’s name, their kids, their pets. now we’re at Walgreens where the clerk doesn’t even look up

Leah Doyle December 7, 2025

just talked to my pharmacist about this yesterday 😭 she said she’s been working 60-hour weeks just to break even. we need to support local pharmacies. even if it means paying a little more. they’re the real heroes here

Jacob Hepworth-wain December 8, 2025

the $2 drug list is a good start but it’s voluntary. if PBMs can opt out, it’s just a sticker on a broken system. we need mandatory transparency and real reimbursement tied to actual cost-not some spreadsheet guess from a corporate office in Minnesota

Olivia Gracelynn Starsmith December 10, 2025

it’s easy to blame PBMs but the truth is we’ve let this happen because we assume someone else is handling it. if you’re on Medicare, you have more power than you think. ask questions. demand formulary transparency. your voice matters more than you realize

Alexander Rolsen December 11, 2025

the government lets PBMs make billions while pharmacies starve… and you think this is an accident? no. it’s deliberate. the same people who profit from your insulin cap are the ones setting MAC rates. they want you dependent on the system. they don’t want you to know you can pay cash

Maria Romina Aguilar December 13, 2025

…and yet, somehow, no one ever talks about how the drug manufacturers raise the list price just so they can give bigger rebates… which makes the MAC rate look even lower… which makes the pharmacy lose more… which makes patients think generics are ‘cheap’… when really, the whole thing is a pyramid scheme…

Sam txf December 13, 2025

the entire pharma-industrial complex is a rigged casino. PBMs are the house. Pharmacies are the dealers getting paid in loose change. Patients are the suckers who keep putting money in. And the government? They’re the bouncer who lets it all happen

Alexis Mendoza December 13, 2025

what if we stopped treating medicine like a commodity? what if we treated it like a public good? we don’t charge people to put out fires or fix roads. why do we charge them to stay alive? maybe the real question isn’t how much pharmacies get paid… but why we let anyone profit from basic health

Austin Simko December 14, 2025

the $2 list is a distraction. they’re just trying to make you think they care. wait till you see the hidden fees on your next EOB. they’re already building the next loophole

Michelle N Allen December 15, 2025

i read all this and honestly i just feel tired. i take three generics. i pay whatever they tell me to pay. i don’t have time to fight PBMs or learn formularies. if the system is this complicated, maybe it’s broken beyond repair. just give me a flat $5 co-pay and let me get on with my life