Imagine a child who used to bounce through the halls now dragging their feet, missing classes, or struggling to focus. Sometimes, the problem isn’t just stress or hormones—it’s something happening inside the body, quietly flipping switches that control energy, bones, and moods. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is one of those invisible conditions school staff rarely see coming, but it’s more common than you’d think, especially in kids with chronic illnesses.

What Is Secondary Hyperparathyroidism?

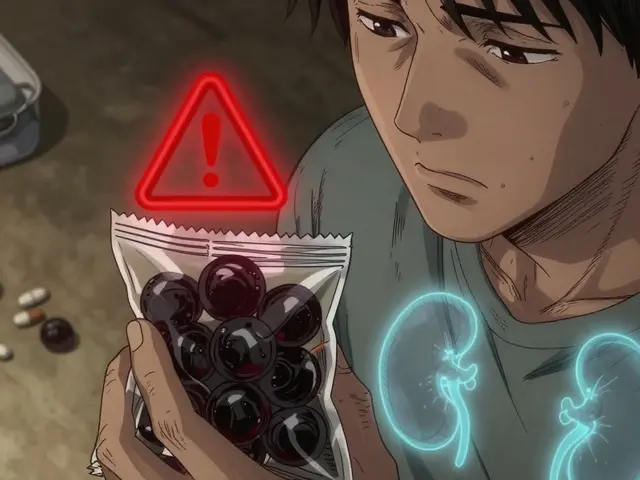

Secondary hyperparathyroidism sounds like a mouthful, right? But it boils down to the body’s way of dealing with low calcium. See, the parathyroid glands—these teensy organs about the size of a grain of rice tucked behind the thyroid—keep tabs on calcium levels in the blood. When something (often chronic kidney disease) stops the body from balancing calcium and phosphorus, these glands start pumping out extra parathyroid hormone (PTH). Too much PTH, and you get all sorts of knock-on effects, like brittle bones, muscle weakness, and nerve problems.

You’d expect a problem like this to show up only in older folks, but it’s actually pretty common in children and teens with chronic kidney issues. National Kidney Foundation numbers put the risk at nearly 60% in kids at later stages of kidney disease. Not everyone knows that vitamin D deficiency—another cause—can do the same thing, ramping up the glands and setting off symptoms.

The wild thing about secondary hyperparathyroidism is that symptoms can be almost invisible at first. Maybe some trouble with joints, fatigue, achy bones, or a kid saying their legs "just don’t work right today." Over time, though, untreated cases lead to soft, weak bones, stunted growth, and even fractures. No one wants that for their students.

What makes secondary hyperparathyroidism “secondary” is that it’s always triggered by another problem—most commonly kidney disease. The kidneys stop filtering waste properly, and the body starts losing calcium while hanging onto too much phosphorus. This chemical wave basically tricks the parathyroid glands into overdrive. You might notice more frequent bathroom breaks, persistent headaches, or sudden changes in behavior. These aren’t your typical, run-of-the-mill teenager problems.

Diagnosing this condition is usually handled by specialists, but alert school nurses or teachers can be the first to spot symptoms. Chronic bone pain or consistent fatigue, especially in kids with known kidney problems, should raise a red flag. Sometimes parents haven’t picked up on the extent of the issue, so an observant staff member really can make the difference.

How It Affects Students in the School Environment

Now, picture a young student dealing with this condition. They might stop running at recess, drift off in class, or seem moodier than usual. The changes are subtle, yet can seriously impact how they keep up with schoolwork and friendships.

One surprising fact: up to 30% of kids with chronic kidney disease develop moderate to severe learning difficulties, partly due to mineral imbalances like those caused by secondary hyperparathyroidism. Frequent fatigue and musculoskeletal pain might cause students to miss classes or avoid activities they once loved. Sometimes, teachers notice handwriting that used to be neat becoming shaky or hard to read because the small muscles in the hands are affected.

Absences are another real concern. A student with secondary hyperparathyroidism may have to leave class for medical appointments, or just stay home because of bone pain or exhaustion. Even when they’re present, “brain fog” from fluctuating blood chemistry can make concentrating tough. Suddenly, homework deadlines feel impossible, friends grow distant, and confidence fades. It’s way more than just the physical aches.

Mental health issues can follow. Kids may get frustrated with their bodies, feel singled out, or be embarrassed by the changes they can’t control. It’s not uncommon for students with chronic conditions—including this one—to feel isolated, anxious, or even depressed. Teachers and nurses are often first to notice these signals, because they’re in prime position to spot mood swings, flat affect, or withdrawal from group activities.

School staff have a big opportunity here. Being sensitive to changes, making adaptations in PE or classwork, and keeping a line of communication open with parents and medical teams can ease a student’s experience. Something as simple as extra time for assignments, a bathroom pass, or an understanding nod can change the course of their school year.

Early Warning Signs and When to Take Action

If you’ve ever wondered when a limp, yawn, or blank stare is more than just Monday morning blues, here’s what to look for.

- Persistent or unexplained bone or joint pain

- Sudden muscle weakness, especially after normal activities

- Fatigue that doesn’t get better with rest

- Recurring headaches or abdominal pain

- Disrupted growth or delays in height/weight gain

- Mood changes—irritability, sadness, or unexplained anger

- Noticeably soft or bent bones (particularly in the arms and legs)

- Frequent fractures or injuries from minor accidents

If a student you know is already being treated for kidney disease, vitamin D deficiency, or has mentioned parathyroid issues at home, these signs are even more important. Don’t hesitate to talk to parents or recommend a medical check. Sometimes it takes that nudge from school to get the ball rolling.

Screening for this condition typically involves basic blood tests to check for calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, and PTH levels. Most kids won’t need these checks unless they have an underlying risk, but awareness matters. Teachers and school nurses can log observations of symptoms and report them back to parents or pediatricians, giving doctors the information they need for an accurate diagnosis.

Documenting changes—like a noticeable slump in academic or physical performance—helps so much more than people think. If you notice patterns (for example, the student’s pain is worse after PE or worsens later in the week), keeping these notes updated supports both the family and medical team. You’re not diagnosing, but your outside perspective gives another piece of the puzzle.

Practical Tips for School Nurses and Educators

Supporting students with secondary hyperparathyroidism isn’t about memorizing medical texts or acting as doctors. Instead, it’s about adapting the classroom, routines, and attitudes to help kids shine despite the setbacks.

- secondary hyperparathyroidism education: Train your staff on what this condition looks like and why it matters. Offer easy-to-understand guides or quick chats so everyone’s on the same page.

- Adapt PE and physical activities: It’s not about excluding students, but working with them (and their medical plan) for what’s safe. Replace running laps with lower-impact alternatives or allow rest breaks.

- Flexible assignments: Some days, students simply won’t feel up to completing everything. Offer extensions or alternate assignments without fuss.

- Bathroom access: Let these students use the facilities when they need to—they may struggle with urinary frequency due to kidney issues.

- Health monitoring: Set up simple check-ins. A private ‘how are you feeling?’ can go a long way in building trust and catching early warning signs.

- Emotional support: Encourage regular communication with the student and their family. Consider peer support systems so the student doesn’t feel alone.

- Advocacy: Help families navigate IEPs (Individualized Education Programs) or 504 Plans to secure needed accommodations and protect the student’s rights.

- Awareness materials: Post infographics or share pamphlets in staff areas so everyone knows what to look out for.

- Medical alert: With parent permission, list pertinent health info with the front office in case of emergency so staff know how to respond.

It sounds like a lot, but small changes add up. Allowing water bottles in class, checking in discreetly after recess, or providing a quiet spot for rest can all help. Remember, school staff are often the first line of defense for kids’ well-being, and you don’t need a medical degree to make a difference. Your compassion and awareness might be what keeps a student on the path to both academic and physical success.

Building Awareness and Creating a Safer School Community

One little-known fact: less than 10% of teachers feel prepared to recognize chronic metabolic conditions in their students, according to a 2022 survey by the National School Health Association. But that’s easy to change. Building awareness starts with simple conversations and basic training sessions—no need for hour-long lectures or complicated terminology.

Mark days on the school calendar for health screenings or chronic illness awareness. Invite guest speakers or local health professionals to present short talks. Provide resources that are clear and easy to use, so staff never feel overwhelmed. Put together an emergency response plan for students with chronic illnesses—just like you would for allergies or epilepsy.

Ongoing communication is everything. Chat with parents, check in with medical teams, and include students in conversations about their health. Sometimes, just knowing someone cares is enough to encourage self-advocacy or honest conversations about symptoms. Celebrate your students’ wins and support them during flare-ups. Build a buddy system so classmates understand and can help each other.

Documenting, noticing, and sharing patterns isn’t just about being thorough—it’s about giving every student the best shot at a healthy, happy school experience. The sooner you spot a problem, the sooner that student can get the support and treatment they need. And trust me: for kids fighting invisible battles, an empathetic, educated adult can be the difference between slipping through the cracks and finding their stride again.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is treatable and manageable, especially when a caring team gets involved. Schools are more than just classrooms—they’re safety nets, scaffolds, and sanctuaries. And every little thing educators and nurses do makes a world of difference for students facing these hidden health hurdles.

Gayle Jenkins July 23, 2025

This is exactly the kind of guide every school needs printed and taped to the nurse’s station. I’ve seen kids labeled as 'lazy' or 'disengaged' when they were just suffering in silence from mineral imbalances no one thought to check. Thank you for making this visible.

Kaleigh Scroger July 24, 2025

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is underdiagnosed in pediatrics because it doesn't present like textbook cases and school staff aren't trained to connect fatigue or mood swings to endocrine dysfunction. The fact that 60% of kids with advanced kidney disease develop this means we're missing a huge population of students who need support. Training modules should be mandatory for all school nurses and even homeroom teachers. It's not about becoming medical experts it's about recognizing red flags and knowing when to escalate. Documentation matters too. A simple log of daily energy levels or complaints of bone pain over weeks can be the key that unlocks diagnosis. Parents are often overwhelmed and don't realize how much their child's school life is affected. We can bridge that gap.

laura lauraa July 25, 2025

Oh, wonderful. Another sanctimonious guide for educators to feel morally superior while doing absolutely nothing structural to fix the broken healthcare system that lets children suffer in plain sight. You tell teachers to 'notice' symptoms... but who pays for the blood tests? Who ensures insurance covers the specialists? Who gives kids the time off without punishment? You're not solving anything-you're just making teachers feel guilty for not being unpaid medical detectives.

Elizabeth Choi July 26, 2025

Let’s be real-this article is just a thinly veiled push to expand school-based medical surveillance. Next thing you know, we’ll have nurses running calcium panels on kids who yawn too much. It’s not about helping students-it’s about pathologizing normal adolescent behavior under the guise of ‘awareness.’

Allison Turner July 28, 2025

Why are we even talking about this? Kids are tired because they’re on their phones all night. Bone pain? Probably from backpacks. This is just medicalizing normal teen stuff. Stop overcomplicating everything.

Darrel Smith July 29, 2025

Let me tell you something-this country is falling apart because we’ve turned schools into clinics and teachers into nurses. Kids these days are weak. Back in my day, we walked five miles uphill both ways and didn’t complain about a little fatigue. Now we’re giving out bathroom passes and extensions because some kid has a hormone problem? What happened to resilience? This isn’t compassion-it’s coddling.

Aishwarya Sivaraj July 29, 2025

As a teacher in rural India I’ve seen kids with chronic illness go unnoticed because families can’t afford tests or doctors don’t have time. This article is a lifeline. Even small things like letting a child sit quietly during PE or allowing extra water breaks make a difference. We don’t need to diagnose-we just need to see. Thank you for writing this. I’ll share it with every teacher I know

Iives Perl July 29, 2025

They’re hiding the truth. This isn’t just kidney disease. It’s fluoride in the water. GMOs in the school lunch. The government is poisoning kids to push vaccines. Check the PTH levels in Flint. Coincidence? I think not. 😈

steve stofelano, jr. July 30, 2025

While the intent of this publication is laudable and reflects a commendable commitment to student well-being, one must acknowledge the structural limitations inherent in the American educational infrastructure. Without systemic funding for school-based endocrinology screening programs, the burden of early detection remains disproportionately placed upon under-resourced personnel. A policy-oriented supplement to this guide would significantly enhance its utility.

Savakrit Singh July 31, 2025

Interesting article. But let’s be honest-this is just another Western medical narrative. In India, we don’t have the luxury of blood tests for every tired kid. We teach resilience. You can’t fix everything with a 504 plan. 😔

Cecily Bogsprocket August 1, 2025

I’ve had students like this. One girl stopped playing violin because her hands hurt too much. No one knew why. We just thought she was losing interest. Then her mom mentioned kidney issues. Once they started treatment, she came back-quietly, slowly, but she came back. It’s not about grand gestures. It’s about showing up. Asking how they are. Not once. Every day. That’s what changes things.

Jebari Lewis August 2, 2025

As someone who works with at-risk youth, I’ve seen how invisible illnesses destroy academic momentum. This guide is vital. But let’s push further-why aren’t we training all school staff on metabolic disorders as part of basic health literacy? Why is this still considered niche? We need mandatory annual workshops. I’ll draft a curriculum if anyone wants to collaborate.

Emma louise August 3, 2025

Oh great, now we’re teaching kids they can’t even be tired without a diagnosis. Next they’ll be handing out IEPs for being ‘emotionally exhausted’ because they didn’t get enough TikTok likes. This is why America is collapsing.

sharicka holloway August 4, 2025

My niece has this. She used to be the first one on the soccer field. Now she sits on the bench and just stares. Her teacher noticed. Didn’t make a big deal. Just asked if she wanted to sit out. That’s all it took. Sometimes being seen is enough.

Alex Hess August 5, 2025

Pathetic. A 12-page pamphlet on how to spot a rare endocrine disorder in children? This is what passes for education now? Any idiot with Google can look up PTH levels. Why are we paying teachers to be amateur endocrinologists? This is performative allyship at its worst.

Lauren Zableckis August 7, 2025

I appreciate the effort here, but I wonder if we’re missing the bigger picture. What if we stopped focusing so much on diagnosing and started focusing on building flexible, resilient school environments where kids with any kind of chronic condition-seen or unseen-can thrive without needing a label? Maybe that’s the real solution.

Gayle Jenkins August 8, 2025

Exactly. You don’t need to know the name of the disease to see when a kid is struggling. You just need to care enough to ask. And then act-without waiting for a diagnosis.

Cecily Bogsprocket August 9, 2025

My favorite thing? When the kid who used to hide in the back of class starts raising their hand again-not because they’re cured, but because they finally feel safe enough to try.