Rational Combination Checker

Check Your Combination Drug

Enter the active ingredients of your combination drug to evaluate if it meets scientific criteria for safe and effective use.

Enter ingredients to see evaluation results.

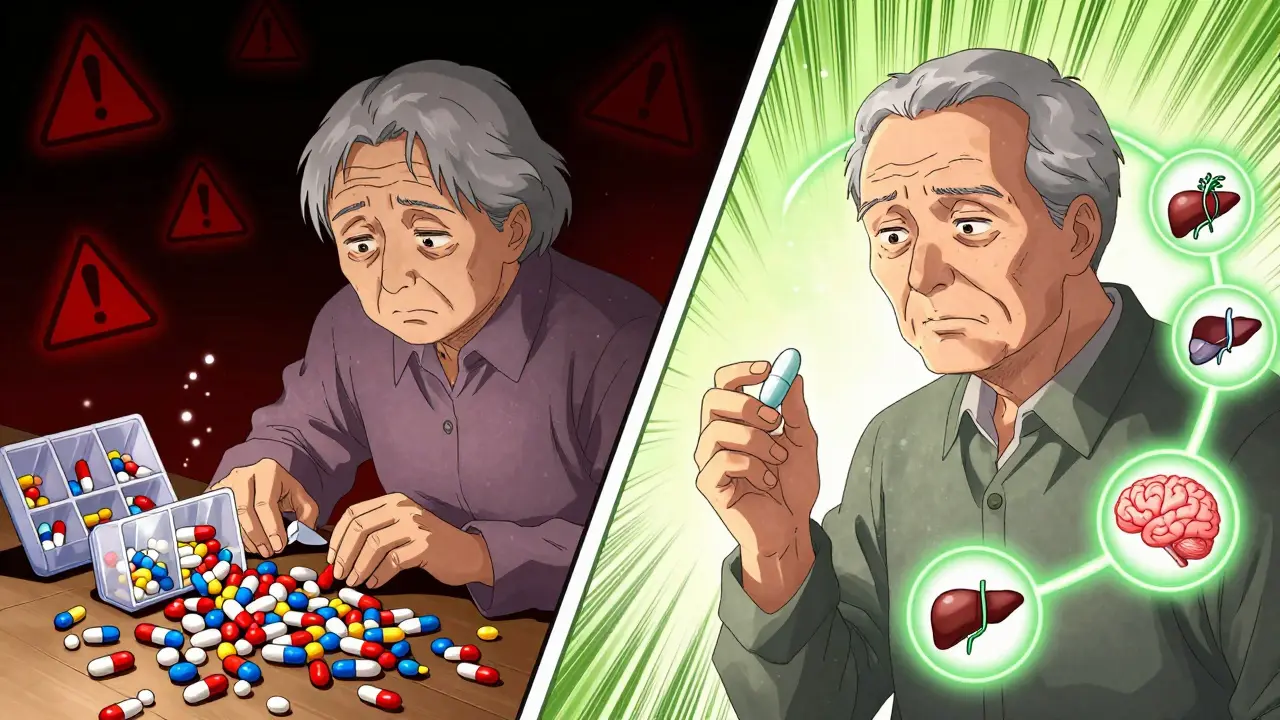

Imagine taking five pills a day just to manage your blood pressure, diabetes, and cholesterol. Now imagine taking just one. That’s the promise of combination drugs - also called fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) - and it’s why millions of people around the world use them every day. But behind the simplicity lies a complex trade-off: convenience versus risk. Are these multi-drug pills a lifesaver, or are they hiding dangers we’re not talking about enough?

What Are Combination Drugs, Really?

Combination drugs pack two or more active ingredients into a single tablet, capsule, or injection. They’re not new. Traditional medicine systems like Traditional Chinese Medicine used multi-herb formulas centuries ago. But modern FDCs started taking shape in the 1970s with drugs like sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim - a combo that fights bacterial infections better than either drug alone.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized these combinations for decades. Back in 2005, their Essential Medicines List included 18 fixed-dose combinations out of 312 total formulations. Today, that number has grown. Why? Because they work - especially for chronic conditions where patients need to take multiple drugs daily.

Common examples include:

- Levodopa + carbidopa for Parkinson’s disease

- Rifampicin + isoniazid for tuberculosis

- Hydrochlorothiazide + lisinopril for high blood pressure

- Metformin + sitagliptin for type 2 diabetes

Each of these combos was carefully tested. The ingredients were chosen because they work together - targeting different parts of the disease, having similar timing in the body, and not making each other more dangerous than they already are.

The Big Win: Less Pill Burden, Better Adherence

One of the clearest benefits? Fewer pills. A study published in 2020 showed patients on combination drugs were 25% more likely to stick to their treatment than those taking the same drugs separately. Why? Because forgetting one pill out of five is way easier than forgetting one out of one.

For older adults or people managing multiple chronic conditions, this isn’t just a convenience - it’s a lifeline. When patients take their meds as prescribed, hospital visits drop, complications slow down, and lives get longer. That’s why the WHO and the FDA both support rational FDCs. In places with limited healthcare access, like rural India or sub-Saharan Africa, combination drugs have helped tuberculosis treatment completion rates jump by over 30%.

It’s not just about pills. It’s about dignity. No more juggling a pill organizer with 10 compartments. No more explaining to your family why you take so many things every morning. One pill. One routine. One less thing to stress about.

The Hidden Costs: When One Drug Goes Wrong, the Whole Thing Stops

But here’s the flip side. If one ingredient in the combo causes a bad reaction - say, a rash, dizziness, or kidney stress - you can’t just stop that one drug. You have to stop the whole thing. And that means going back to square one: figuring out which drug caused the problem, then re-prescribing each one separately, at the right dose.

This is a major problem in real-world practice. Take a 70-year-old with high blood pressure on a combo of amlodipine and valsartan. If they develop ankle swelling from the amlodipine, their doctor can’t just lower the dose. They have to switch to a different combo or go back to two separate pills. That’s disruptive. It’s confusing. And it can lead to dangerous gaps in treatment.

Worse, some combinations aren’t even scientifically sound. In countries like India, regulators have had to ban over 300 FDCs in the last decade because they were “irrational” - meaning no proven benefit, or worse, hidden risks. Some contained outdated antibiotics, others mixed drugs with conflicting effects. These aren’t just bad science - they’re fueling antimicrobial resistance, a global crisis the WHO calls one of the top 10 public health threats.

Why Some Combinations Work - and Others Don’t

Not all FDCs are created equal. A good combination follows strict rules:

- Each drug should attack the disease in a different way

- The drugs should stay in the body for roughly the same amount of time

- The doses should be safe when taken together - not add up to something toxic

- There should be clinical proof the combo works better than either drug alone

For example, levodopa + carbidopa works because carbidopa blocks the breakdown of levodopa in the bloodstream, letting more of it reach the brain. That’s smart design. It’s not just mixing two drugs - it’s engineering a better outcome.

On the other hand, some FDCs for colds or allergies combine antihistamines, decongestants, and painkillers - even though most people don’t need all three. These are often marketed for convenience, not medical need. And they’re the ones that end up causing more side effects than they prevent.

Regulation: Who’s Watching the Store?

In the U.S., the FDA treats combination drugs as new entities. That means even if each ingredient has been approved separately, the combo must prove its own safety and effectiveness. The agency doesn’t just look at the ingredients - it looks at how they interact, how they’re absorbed, and whether the final product is stable and consistent.

But not every country has the same standards. In some places, FDCs flood the market without proper testing. The Indian drug regulator CDSCO has repeatedly pulled unsafe combinations off shelves. Meanwhile, in the U.S., compounded medications - custom mixes made by pharmacists - are a different story. These aren’t FDA-approved. The agency doesn’t check their safety before they’re sold. That’s why you won’t find a compounded cream with amitriptyline, baclofen, and ketamine in a pharmacy aisle - it’s made only for specific patients under a doctor’s order.

The key difference? FDCs are mass-produced, regulated, and tested. Compounded drugs are personalized, unregulated, and rare. Mixing them up can be dangerous.

Where Are We Headed?

The future of combination drugs isn’t about more pills - it’s about smarter pills. Companies are now using AI to predict which drug pairs will work best together, especially for rare diseases where traditional trials are too slow. Researchers are testing combinations for cancer, Alzheimer’s, and autoimmune disorders that target multiple pathways at once - something single drugs can’t do.

The WHO is expected to update its Essential Medicines List in 2025, likely adding more evidence-based FDCs. But they’re also cracking down harder on irrational ones. The goal isn’t to ban combos - it’s to make sure only the good ones stay on the market.

For patients, the message is simple: Don’t assume a combo is better just because it’s one pill. Ask your doctor: Is this combo proven to work better than separate drugs? What happens if I have a reaction to one ingredient?

For prescribers, the message is even clearer: Don’t prescribe a combination unless you can justify it. If you’re choosing it for convenience alone - and not because the science supports it - you’re risking more harm than help.

What Should You Do?

If you’re on a combination drug:

- Know exactly what’s in it. Ask your pharmacist for the list of active ingredients.

- Watch for new side effects after starting the combo - especially in the first few weeks.

- Don’t stop it without talking to your doctor. Even if one part seems to be causing trouble, there might be a safer alternative.

- Keep a list of all your meds. If you’re seeing multiple doctors, make sure they all know you’re on a combination pill.

If you’re considering switching to a combo:

- Ask: “Is there data showing this combo improves outcomes over separate drugs?”

- Ask: “What if I need to change the dose of one drug later?”

- Ask: “Is this on the WHO Essential Medicines List?” If yes, it’s been vetted globally.

Combination drugs aren’t good or bad. They’re tools. And like any tool, they’re only as safe as the person using them - and the science behind them.

Are combination drugs safe?

Combination drugs are safe when they’re scientifically justified and properly regulated. Many, like those for tuberculosis, high blood pressure, and Parkinson’s, have saved millions of lives. But unsafe or irrational combinations - especially those without clinical proof - can cause harm. Always check if the combo is on the WHO Essential Medicines List or approved by your country’s drug agency.

Can I split or crush a combination pill?

Never split or crush a combination pill unless your doctor or pharmacist says it’s safe. Some pills have special coatings or timed-release systems. Crushing them can change how the drugs are absorbed, making one ingredient too strong or too weak. This can lead to side effects or treatment failure.

Why do some doctors prefer separate pills over combination drugs?

Doctors may prefer separate pills when they need to adjust doses individually. For example, if a patient’s blood pressure improves but they develop swelling from one component, the doctor can lower just that drug’s dose. With a combo, they can’t - they have to switch the entire pill. This is especially important for older adults or people with kidney or liver problems.

Do combination drugs cause more side effects than single drugs?

Not necessarily - but the risk is higher if the combo is irrational. When two drugs are well-matched, side effects are often similar to taking them separately. But if the drugs interact poorly or one is unnecessary, side effects can increase. Studies show that irrational combinations are linked to more adverse reactions than single-agent therapy.

How do I know if my combination drug is approved and safe?

Check if it’s listed on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines or approved by your national drug regulator (like the FDA in the U.S. or MHRA in the UK). You can also ask your pharmacist to confirm the drug’s approval status. If it’s a newer combo, look for clinical trial data or guidelines from major medical societies. Avoid combinations that are only sold in countries with weak regulatory oversight.

Joy Nickles December 31, 2025

so i just took my combo pill for bp and diabetes and honestly? i forgot i was even on two meds until my pharmacist asked if i wanted to split them back up. like... why complicate life? i’m not a chemist, i’m just trying not to die. 🤷♀️

Darren Pearson January 2, 2026

The fundamental flaw in the public discourse surrounding fixed-dose combinations lies in the conflation of convenience with clinical superiority. While adherence metrics may improve, one must interrogate whether this improvement is attributable to pharmacological synergy or merely behavioral inertia. The WHO’s endorsement, while authoritative, does not obviate the necessity for individualized therapeutic assessment.

Urvi Patel January 2, 2026

in india we banned 300+ of these junk combos because pharma companies were selling poison as medicine and now you americans act like its some genius innovation? you dont even regulate compounded stuff properly and you wonder why people die from polypharmacy? fix your own house first

anggit marga January 4, 2026

you think america is the only one with bad drugs? we have people in rural nigeria taking combo pills with expired antibiotics and no idea what theyre even for. the real problem isnt the combo its the system that lets this happen anywhere. we need global standards not western finger pointing

Emma Hooper January 5, 2026

I mean... honestly? If you're on a combo pill and you start feeling like your face is melting or your kidneys are doing the cha-cha, you don't get to just tweak one ingredient. You have to restart the whole damn puzzle. And guess what? Your doctor might not even know what's in it. I had a friend who got hospitalized because her 'blood pressure combo' had a hidden diuretic that tanked her potassium. She didn't even know it was in there. And now? She's got a new pill organizer. And a lawsuit.

Harriet Hollingsworth January 7, 2026

People don’t realize that taking one pill doesn’t make you responsible. It makes you complacent. You stop asking questions. You stop tracking side effects. You assume the doctor did the work. But the truth? Most doctors are overworked, underpaid, and pressured by pharmaceutical reps pushing the newest combo. You think you’re saving time? You’re just handing over your health to a marketing campaign.

Deepika D January 7, 2026

hey everyone! just wanted to share something that changed my life. my dad was on 7 pills a day for diabetes, bp, and cholesterol. he was always confused, kept missing doses, and got really down about it. then his doctor switched him to a metformin + sitagliptin + empagliflozin combo. one pill. morning. done. he started taking his meds like clockwork. his A1c dropped. he started walking again. he said it felt like he got his life back. yes, combos aren’t perfect-but when they’re done right? they’re magic. ask your doc if yours is on the WHO list. if not, push for it. you deserve better than a pill organizer with 12 slots 😊

Chandreson Chandreas January 8, 2026

it’s funny how we treat medicine like a vending machine. you want less hassle? here’s a single button. but life isn’t a vending machine. bodies aren’t widgets. sometimes you need to adjust one thing without touching the others. still... i get it. one pill feels like peace. i take my combo for tb and i don’t think about it. that’s the gift. just don’t forget it’s still medicine. not a spell 🙏

Stewart Smith January 9, 2026

i used to think combo pills were lazy medicine. then my mom got one for her bp and suddenly she wasn’t forgetting half her meds anymore. she started cooking again. went on a cruise. i didn’t think a pill could do that. but it did. so yeah... maybe convenience isn’t the enemy. maybe it’s the bridge.

Retha Dungga January 10, 2026

we are all just trying to survive systems that treat us like data points not humans and if one pill helps you feel less like a pharmacy employee then isnt that a form of liberation? the system failed us first

Jenny Salmingo January 11, 2026

i’m from the philippines and we use these combo pills all the time. my abuela takes one for her diabetes and bp. she doesn’t know the names of the drugs but she takes it every morning like a prayer. sometimes that’s enough. maybe we don’t need all the science to know what helps people live.

Aaron Bales January 12, 2026

if your combo pill isn’t on the WHO essential list, don’t take it. period. if your doctor can’t tell you why it’s better than separate drugs, ask for a different option. your health isn’t a cost-saving experiment.

Lawver Stanton January 13, 2026

i read this whole thing and i’m just wondering-how many people have died because some corporate chemist thought ‘hey, let’s throw this antibiotic in with this blood pressure pill because it’s easier to market’? and now we’ve got superbugs because of it? and nobody’s held anyone accountable? this isn’t medicine. it’s a corporate horror movie and we’re all just sitting here taking the popcorn.

Sara Stinnett January 14, 2026

The very premise of this article is dangerously naive. It treats combination drugs as neutral tools, when in reality they are instruments of pharmaceutical consolidation-designed to extend patent life, suppress generic competition, and commodify patient compliance. The WHO’s inclusion of certain FDCs is not a stamp of ethical approval, but a reflection of pragmatic triage in resource-poor settings. To praise convenience as inherently virtuous is to surrender medical autonomy to the profit motive. This isn’t innovation. It’s enclosure.