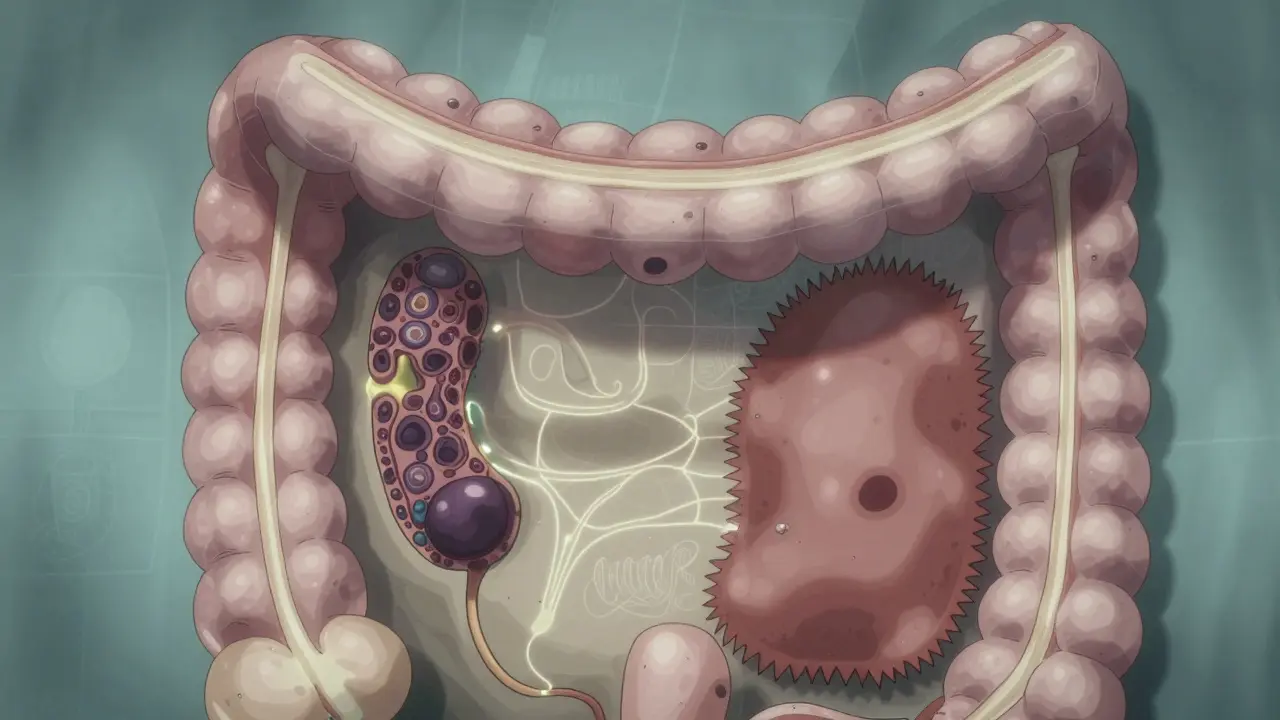

What Are Colorectal Polyps?

Colorectal polyps are small growths that stick out from the inner lining of your colon or rectum. They’re common-about 30 to 50% of adults will develop at least one by age 60. Most don’t cause symptoms, which is why screening is so important. Not all polyps turn into cancer, but some do. The two main types that matter most are adenomas and serrated lesions. These aren’t cancer yet, but they’re the main precursors to colorectal cancer. If caught and removed early, your risk drops dramatically.

Adenomas: The Classic Precancerous Polyp

Adenomas make up about 70% of all precancerous polyps. They’re the type doctors have been watching for decades. Under the microscope, they look like disorganized gland structures. There are three subtypes, and their shape tells you how risky they are.

- Tubular adenomas (70% of adenomas): These are the most common and least dangerous. If they’re smaller than half an inch, the chance of cancer is less than 1%.

- Tubulovillous adenomas (15%): A mix of tubular and finger-like (villous) growth. These carry a higher risk, especially if they’re bigger than 1 cm.

- Villous adenomas (15%): These are flat, spread out, and harder to remove completely. They have the highest cancer risk. If one is larger than 1 cm, there’s a 10-15% chance it already contains cancer cells.

Size matters. A polyp under 0.5 cm is usually low risk. One over 1 cm? That’s when you need to pay attention. Villous features increase cancer risk by 25-30% compared to purely tubular ones of the same size. That’s why complete removal during colonoscopy is critical.

Serrated Lesions: The Stealthy Pathway to Cancer

Serrated lesions are less common but just as dangerous. They cause 20-30% of all colorectal cancers. Their name comes from their "saw-tooth" edge under the microscope. There are three types:

- Hyperplastic polyps: These are usually harmless, especially if they’re small and found in the lower colon. They rarely turn cancerous.

- Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps): These are the big concern. They’re flat, often hidden in the upper colon (cecum and ascending colon), and easy to miss during colonoscopy. About 68% are located above the splenic flexure. They grow slowly but can turn into cancer through a different molecular path than adenomas.

- Traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs): These are rarer but aggressive. They often appear in the left colon and have a higher chance of dysplasia.

Here’s the scary part: SSA/Ps have a cancer risk nearly equal to adenomas. One study found 13% of SSA/Ps had high-grade dysplasia or cancer-almost the same as the 12.3% seen in conventional adenomas. Yet, because they’re flat and blend into the colon wall, they’re missed in 2-6% of colonoscopies. That’s why advanced imaging and experienced endoscopists matter.

Why Detection Is So Hard

Not all polyps are created equal when it comes to visibility. Polyps come in three shapes:

- Pedunculated: Grow on a stalk. Easy to spot and remove.

- Sessile: Flat on the surface. Harder to see, especially if they’re small.

- Flat: Flush with the colon lining. The hardest to detect.

SSA/Ps are mostly sessile or flat. They don’t stick out like a mushroom-they spread out like a stain. That’s why standard colonoscopy misses them. Even with high-quality scopes, up to 1 in 20 serrated polyps go unnoticed. That’s why newer tools like AI-assisted colonoscopy (like GI Genius) are making a difference. Studies show they boost adenoma detection by 14-18%, and they help spot subtle serrated lesions too.

How They Turn Into Cancer

Adenomas and serrated lesions follow different paths to cancer.

Adenomas usually follow the chromosomal instability pathway. This means they pick up mutations in genes like APC and KRAS. It’s a step-by-step process: normal tissue → adenoma → advanced adenoma → cancer. This path takes about 10-15 years.

Serrated lesions follow the serrated pathway, driven by BRAF gene mutations and widespread DNA methylation (called CIMP). This path can skip the classic adenoma stage and jump straight to cancer faster in some cases. That’s why a small SSA/P can be more dangerous than a larger tubular adenoma-it’s not about size alone, it’s about biology.

Knowing the molecular type helps predict risk. In the next few years, labs will routinely test removed polyps for BRAF, KRAS, and methylation markers to guide how often you need follow-up colonoscopies.

What Happens After a Polyp Is Found

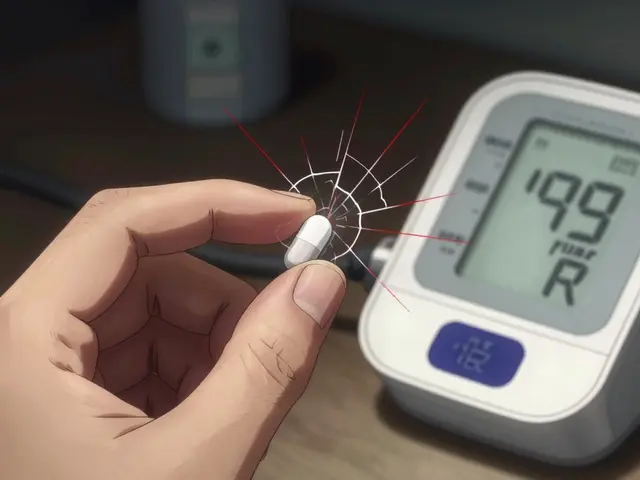

Once a polyp is removed, the big question is: when do you come back?

The American Cancer Society and major U.S. guidelines say:

- If you had 1-2 small tubular adenomas (< 1 cm), come back in 7-10 years.

- If you had 3-10 adenomas, or any larger than 1 cm, come back in 3 years.

- If you had one or more SSA/Ps ≥10 mm, come back in 3 years (per U.S. guidelines).

- If you had multiple SSA/Ps or SSA/Ps with dysplasia, come back in 1-3 years.

Some European guidelines suggest 5 years for SSA/Ps, but U.S. doctors lean toward caution. Why? Because missing one SSA/P could mean missing a cancer years later. The goal isn’t just to remove polyps-it’s to prevent cancer before it starts.

Do Polyps Always Lead to Cancer?

No. Most people with polyps never get colon cancer. But having one increases your risk. Someone with a history of serrated polyps has a 1.5 to 2.5 times higher risk than someone with none. That doesn’t mean you’ll get cancer-it means you need to stay on top of screening.

As Dr. Elizabeth Platz from Johns Hopkins says: "These are precancerous, not cancer. Most patients with polyps never develop cancer." But the key word is "most." And for the ones who do, early detection saved their life.

What You Can Do

Screening is your best defense. If you’re 45 or older, get a colonoscopy. If you have a family history of polyps or colorectal cancer, start even earlier. If you’ve had any polyp removed, follow your doctor’s surveillance schedule. Don’t skip it.

There’s no magic diet or supplement that prevents polyps. But quitting smoking, limiting alcohol, staying active, and eating more fiber can help lower your overall risk. The real game-changer? Getting screened and having polyps removed before they turn dangerous.

Colorectal cancer rates have dropped by 3% per year since 2010 in people over 55-thanks to screening and polyp removal. But rates are rising in younger adults under 50. That’s why knowing your polyp type matters more than ever.

Key Takeaways

- Adenomas and serrated lesions are the two main precancerous polyps.

- Adenomas are more common (70% of cases); serrated lesions cause 20-30% of cancers.

- Size and shape matter: larger and villous adenomas carry higher risk.

- SSA/Ps are flat, hidden, and easy to miss-especially in the right colon.

- Both types need complete removal. Leaving even a small piece behind raises cancer risk.

- Follow-up colonoscopies are tailored to polyp type, size, and number.

- Most polyps don’t become cancer-but catching them early prevents the ones that might.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all colon polyps dangerous?

No. Most colon polyps are harmless. Only adenomas and certain serrated lesions (like SSA/Ps and TSAs) are considered precancerous. Hyperplastic polyps, especially small ones in the lower colon, rarely turn into cancer. But because doctors can’t always tell just by looking, all polyps are removed and tested to be sure.

Can a polyp come back after it’s removed?

The polyp itself won’t grow back in the same spot. But new polyps can form elsewhere in the colon. That’s why follow-up colonoscopies are so important. If you had one adenoma or serrated polyp, you’re at higher risk for developing more over time. Regular screening catches them early before they become dangerous.

Do I need a colonoscopy if I have no symptoms?

Yes. Most polyps cause no symptoms at all. By the time you notice bleeding, changes in bowel habits, or anemia, the cancer may already be advanced. That’s why screening starts at age 45-even if you feel perfectly fine. Colonoscopy is the only test that finds and removes polyps in one step.

What’s the difference between a sessile and a pedunculated polyp?

A pedunculated polyp grows on a stalk, like a mushroom. It’s easy to see and remove. A sessile polyp grows flat against the colon wall with no stalk. These are harder to spot and remove completely, especially if they’re large or in the upper colon. Sessile serrated polyps are almost always flat, which is why they’re so easy to miss.

How accurate are colonoscopies at finding polyps?

Standard colonoscopies detect about 85-90% of adenomas, but only 70-80% of sessile serrated lesions. That’s because SSA/Ps are flat and blend into the colon lining. Newer tools like AI-assisted colonoscopy improve detection by 14-18%. The quality of the prep and the experience of the endoscopist also matter a lot. A well-prepped colon and a skilled doctor make all the difference.

Peter Sharplin January 25, 2026

I've seen so many patients panic when they hear 'precancerous'-but honestly, most of these polyps are totally manageable if caught early. The key isn't fear, it's follow-up. I always tell people: if your doc says come back in 3 years, don't wait until the last week of December to schedule it.

Also, don't underestimate how much prep matters. I had one guy miss a 12mm SSA/P because he drank Gatorade instead of the full laxative. Yeah, he thought it was 'fine.' He's back for a repeat next month.

shivam utkresth January 27, 2026

bro this is wild. in india we got like 3 endoscopists per 100k people and half of em don't even know what a sessile serrated lesion is. i had my first colonoscopy at 38 because my uncle died of 'sudden colon cancer' and turns out he had 3 SSA/Ps missed in 2 prior scopes. we need better training, not just more machines. ai is cool but if the doc is distracted by his phone during the pullback, it don't matter.

Joanna Domżalska January 27, 2026

So let me get this straight. You're telling me that we're removing perfectly harmless growths based on some arbitrary size chart and molecular labels that were invented in 2010? And now we're spending thousands on repeat scopes because some guy in a lab said a polyp has 'methylation markers'? This isn't medicine. This is fear-based capitalism dressed up as prevention.

Josh josh January 29, 2026

i got a tubulovillous at 42 and my doc said come back in 3 years. i was like ok but honestly i just wanna know if i can still eat nachos. the answer is yes. just dont smoke and dont pretend you're 25 anymore. also ai colonoscopy sounds like sci fi but if it catches the sneaky flat ones im all for it

bella nash January 29, 2026

The clinical significance of adenomatous and serrated neoplasia cannot be overstated. The molecular divergence between the chromosomal instability pathway and the serrated neoplasia pathway represents a paradigm shift in colorectal carcinogenesis. One must exercise rigorous adherence to surveillance intervals, as temporal noncompliance may result in the progression of high-grade dysplasia to invasive adenocarcinoma.

Furthermore, the anatomical predilection of sessile serrated adenomas for the proximal colon necessitates a meticulous, high-definition withdrawal technique.

Geoff Miskinis January 30, 2026

I find it amusing that American guidelines recommend 3-year intervals for SSA/Ps while the British, who actually understand pathology, still use 5 years. This is what happens when you let committees write medical advice. The data doesn't support such aggressive surveillance. And don't get me started on AI-assisted colonoscopy-more like AI-assisted billing.

Betty Bomber February 1, 2026

my grandma had a polyp removed last year and she’s 81. she said the prep was worse than the procedure. i’m just glad she didn’t skip it. i’m 34 and i’ve been putting off my colonoscopy because i’m scared. but reading this made me realize: if it’s just a tiny thing they can yank out, why am i stressing? i booked mine for next month.

Nicholas Miter February 1, 2026

i used to think colonoscopies were for old people. then i saw my cousin get diagnosed with stage 3 cancer at 39 because he ignored bleeding for a year. turns out he had a big SSA/P that was missed on his first scope.

the truth is: if you’re over 45, get it done. if you’re under 45 and have family history? do it earlier. don’t wait for symptoms. the body doesn’t scream before it collapses.

also, drink all the laxative. even the gross ones. your future self will thank you.

Suresh Kumar Govindan February 2, 2026

This entire system is controlled by Big Pharma and GI equipment manufacturers. The 'serrated pathway' was invented to justify more scopes, more biopsies, more revenue. The real cause of rising colon cancer in young adults? Glyphosate in the food supply and fluoride in the water. No one wants to talk about that.

George Rahn February 2, 2026

Let’s be real-this is why America is falling behind. We’re letting foreigners tell us how to do medicine. The British think 5 years is fine? They’re sleeping on their patients. We don’t cut corners here. We remove every polyp, test every sample, and follow up early because we care about our people. This isn’t just science-it’s American responsibility.

Ashley Karanja February 3, 2026

I just want to say how much this post helped me feel less alone. I had an SSA/P removed last year and I’ve been terrified ever since. I kept wondering if I did something wrong, if my diet caused it, if I’m going to die. But reading this-really reading it-made me realize it’s not my fault. It’s biology. It’s luck. It’s just how the body works sometimes.

And honestly? The fact that we have tools to catch this before it turns into something deadly? That’s kind of beautiful. I’m gonna hug my gastroenterologist next time I see her. 🤗❤️

Aishah Bango February 3, 2026

If you’re not getting screened by 45, you’re being selfish. You think it’s just about you? What about your family? Your kids? Your partner? One missed polyp can leave a widow, an orphaned child, a funeral bill. This isn’t a personal choice-it’s a moral obligation. Stop being lazy. Get screened.