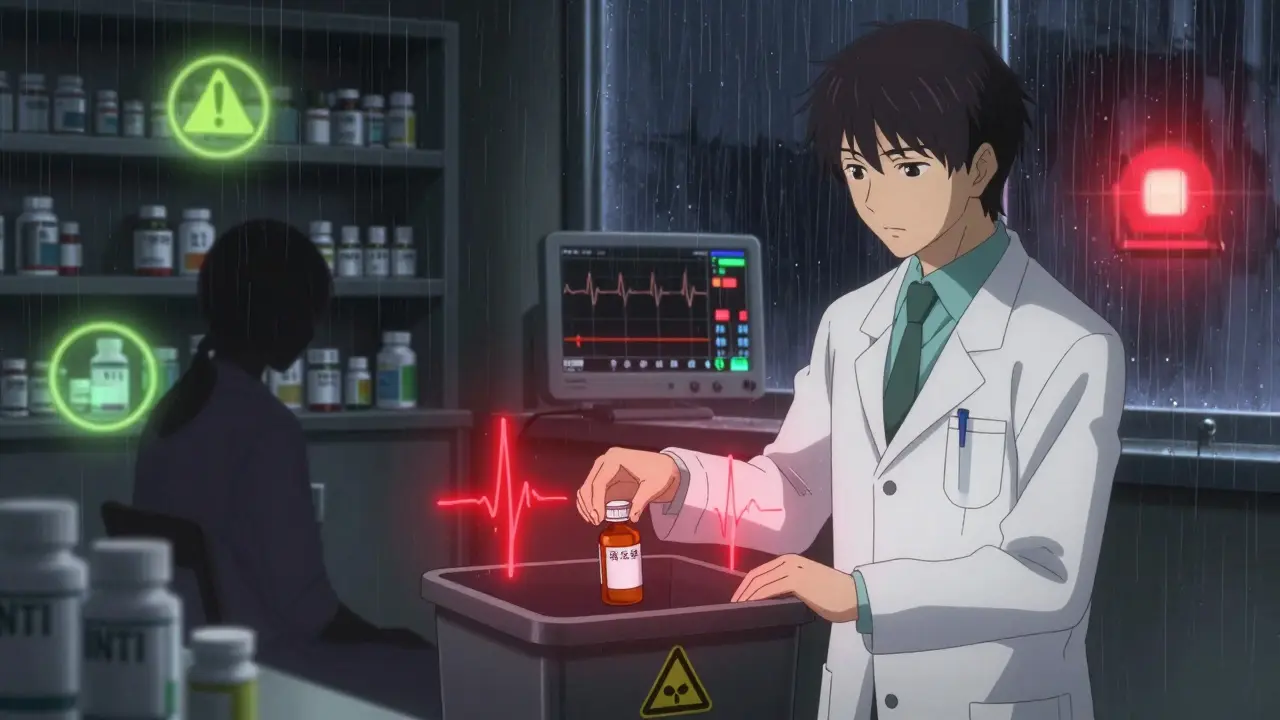

Some medications don’t just lose effectiveness after they expire-they can turn dangerous. This is especially true for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI). These aren’t your typical painkillers or antihistamines. They’re powerful, precise tools used to treat life-threatening conditions. And when they’re even slightly off, the consequences can be fatal.

What Exactly Is a Narrow Therapeutic Index?

A narrow therapeutic index means the difference between a safe, effective dose and a toxic one is tiny. Think of it like walking a tightrope. One step too far, and you fall. For most drugs, your body can handle a bit more or less without harm. But for NTI drugs, even a 10% change in concentration can push you from healing to hospitalization.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration defines NTI drugs as those where small changes in blood levels can cause serious harm-like internal bleeding, seizures, organ failure, or death. Health Canada and the European Medicines Agency agree: if the gap between the minimum effective dose and the minimum toxic dose is less than twofold, it’s an NTI drug.

Common examples include:

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Lithium (for bipolar disorder)

- Digoxin (for heart failure)

- Phenytoin (for seizures)

- Carbamazepine (for epilepsy and nerve pain)

- Levothyroxine (for hypothyroidism)

- Ciclosporin (for transplant patients)

These aren’t optional meds. People taking them rely on them to stay alive. A warfarin patient with a mechanical heart valve needs their INR between 2.5 and 3.5. Go below that, and a clot can form. Go above, and they might bleed internally. That’s a razor-thin margin.

Why Expiration Dates Matter More for NTI Drugs

Every pill has an expiration date. That’s not just a marketing tactic-it’s the last day the manufacturer guarantees the drug will work as intended, assuming it’s been stored properly. For most medications, even after expiration, potency might still be above 90%. But for NTI drugs, that 10% drop could be catastrophic.

Take warfarin. If a tablet loses just 10% of its potency after expiration, a patient taking the same dose as before might suddenly be underdosed. Their INR could drop from 3.0 to 2.2. That might sound small. But for someone with a mechanical valve, that’s enough to trigger a stroke.

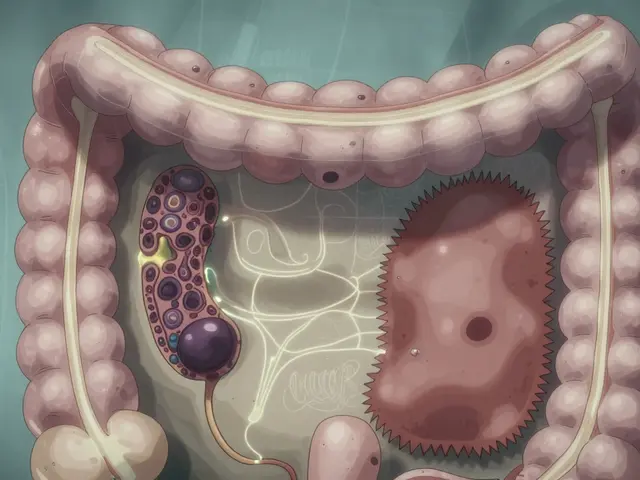

Or consider digoxin. Its therapeutic range is 0.5 to 0.9 nanograms per milliliter. Toxicity starts above 1.2. That’s only a 33% jump from the top of the safe range to the danger zone. If degradation pushes levels even slightly higher-say, due to heat exposure or moisture-the patient could develop nausea, confusion, or fatal heart rhythms.

Lithium is another example. It’s used to stabilize mood in bipolar disorder. Blood levels must stay between 0.6 and 1.0 mmol/L. Too low, and depression or mania returns. Too high, and the patient suffers tremors, kidney damage, or seizures. A degraded lithium tablet might deliver 85% of its intended dose. That’s not a minor issue-it’s a medical emergency waiting to happen.

The FDA’s Strict Rules Show How Precise These Drugs Must Be

The FDA doesn’t treat NTI drugs like ordinary generics. In 2011, they introduced special bioequivalence rules. For most drugs, a generic version must be 80-125% as potent as the brand-name drug to be approved. For NTI drugs? That range is cut to 90-111%. That’s a 25% tighter margin. Why? Because even small differences in formulation or absorption can cause harm.

That same precision applies to expiration. If a drug degrades by 5% past its expiration date, that’s a 45% deviation from the acceptable bioequivalence range for NTI drugs. In other words, an expired NTI medication might be outside the safety parameters the FDA itself requires for brand-new generics.

The FDA has specifically required replicate bioequivalence studies for four NTI drugs: tacrolimus, phenytoin, levothyroxine, and carbamazepine. These aren’t random choices-they’re drugs where tiny changes have been proven to cause real harm in patients.

What Happens When You Take an Expired NTI Drug?

You might think, “It’s just a few months past the date. It can’t be that bad.” But here’s the reality:

- With warfarin: Underdosing increases clot risk. Overdosing increases bleeding risk. Both can kill.

- With lithium: Even a 0.2 mmol/L rise can cause toxicity. Degradation doesn’t always show up as visible changes-no discoloration, no smell.

- With digoxin: Symptoms of toxicity (vomiting, blurred vision, irregular heartbeat) can be mistaken for other illnesses, delaying treatment.

- With levothyroxine: Too little causes fatigue, weight gain, depression. Too much causes heart palpitations, bone loss, atrial fibrillation.

There’s no way to tell if an expired NTI drug is still safe by looking at it. No test strips. No home kits. You can’t measure blood concentration before taking it. The only safe choice is to not take it at all.

What Should You Do?

If you take an NTI medication:

- Never use it past the expiration date. Even if it looks fine, even if it’s only one month past.

- Store it properly. Keep it in a cool, dry place. Avoid bathrooms and kitchens. Heat and moisture speed up degradation.

- Don’t share pills. Even if someone else takes the same drug, their dose is tailored to them. Your levothyroxine isn’t their levothyroxine.

- Ask your pharmacist. If you’re running low, ask if you can get a new prescription early. Most pharmacies will help.

- Dispose of expired meds safely. Take them to a pharmacy drop-off or a drug take-back event. Don’t flush them or toss them in the trash.

Healthcare providers should treat NTI drugs as high-alert medications. That means double-checking prescriptions, verifying doses, and asking patients if their meds are expired. Pharmacists should flag NTI drugs in their systems and warn patients clearly.

Why This Isn’t Just a “Best Practice”-It’s a Safety Standard

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, and the NIH all agree: expired NTI drugs are not worth the risk. The FDA’s own data shows these drugs have low within-subject variability-meaning your body responds the same way every time you take the right dose. But if the dose itself changes due to degradation, that consistency vanishes.

There’s no evidence that NTI drugs remain safe or effective after expiration. And there’s plenty of evidence that even small changes in concentration can lead to death.

It’s not about being overly cautious. It’s about understanding that for these drugs, precision isn’t optional-it’s survival.

What’s Being Done?

Pharmaceutical companies are starting to respond. About 78% of major manufacturers now test NTI drugs for stability beyond their labeled expiration dates. But that’s for inventory control-not for patients keeping pills in their medicine cabinets.

Professional groups like the American Pharmacists Association are pushing for clearer labeling on NTI drugs: “Do not use after expiration” printed in bold, storage instructions on the bottle, and warnings on the packaging.

But until those changes are universal, the responsibility falls on you. If you’re taking one of these drugs, your expiration date isn’t a suggestion. It’s a deadline.