When a drug first hits the market, the company that made it gets a 20-year patent on the active ingredient. That’s the primary patent. But here’s the catch: by the time the drug reaches patients, five or six years have already passed in clinical trials. That leaves maybe 12 to 15 years of real market exclusivity. And that’s not enough for some companies. So they turn to secondary patents-a legal strategy that stretches exclusivity by years, sometimes decades, even after the original patent expires.

What Exactly Are Secondary Patents?

Secondary patents don’t protect the chemical that makes the drug work. They protect everything else: how it’s made, how it’s taken, what form it comes in, or even a new disease it can treat. Think of it like buying a car. The primary patent is the engine. The secondary patents are the leather seats, the GPS system, the extended warranty, or the special paint job. They’re not the core product, but they make it harder for someone else to copy it. The most common types include:- Formulation patents: Protecting a new pill shape, slow-release version, or liquid form. AstraZeneca’s Nexium was a classic example-switching from Prilosec (a mix of two molecules) to just one (esomeprazole) extended exclusivity by eight years.

- Polymorph patents: Covering different crystal structures of the same molecule. GlaxoSmithKline used this to delay generics for Paxil, even after the main patent expired.

- Method-of-use patents: Claiming a new medical use. Thalidomide was originally a sleep aid, but later got patents for treating leprosy and multiple myeloma.

- Combination patents: Protecting a drug paired with another. This is common in HIV and cancer treatments.

- Manufacturing process patents: Even if not listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, these can still block generics by making it harder to replicate the drug.

One drug can have over 100 secondary patents. Humira, AbbVie’s top-selling biologic, had 264 of them. The primary patent expired in 2016. But thanks to this patent thicket, generic versions didn’t arrive until 2023.

Why Do Companies Do This?

It’s not about innovation-it’s about revenue. The top 10 drugmakers hold 73% of all secondary patents. And they’re not random. These patents cluster around drugs that make over $1 billion a year. For every extra billion in annual sales, a company’s chance of filing a secondary patent goes up by 17%, according to a 2012 study in PLOS ONE. The math is simple: a single blockbuster drug like Humira brings in $20 billion a year. Even if a generic cuts that by 80%, that’s still $4 billion in lost revenue. That’s why companies spend $12-15 million per secondary patent application and hire 15-20 patent lawyers per major drug franchise. The strategy works. Drugs with secondary patents see generic entry delayed by an average of 2.3 years longer than those without. And method-of-use patents are especially effective-68% successfully block generics for their specific indications, according to the FDA.The Cost to Patients and Health Systems

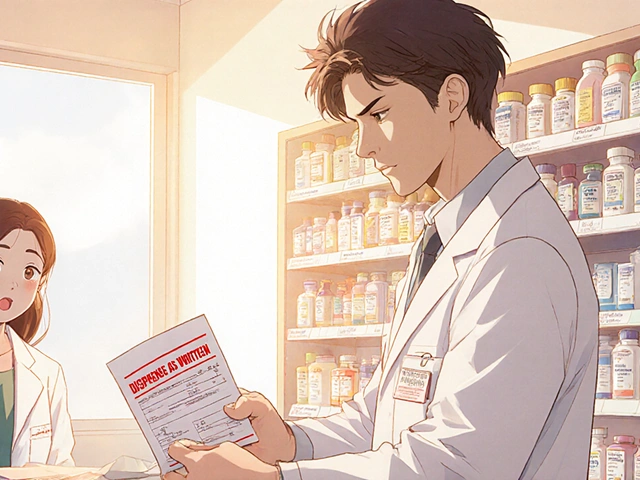

It’s not just big pharma that wins. Patients and insurers pay the price. Pharmacy benefit managers like Express Scripts report that secondary patents raise their annual costs by 8.3%. Generic manufacturers say navigating these patent thickets adds $15-20 million in legal fees and delays market entry by 3.2 years on average. Doctors see it too. Dr. Emily Roberts, a primary care physician in California, told Medscape in 2022 that reps push new formulations right before generics arrive. “Patients get confused,” she said. “They’re told the new version is ‘better,’ but it’s often just the same drug in a different pill.” This tactic, called ‘product hopping,’ pushes people off cheap generics and onto expensive branded versions. Patient groups like Knowledge Ecology International point to Humira again. With 264 patents, the drug cost $20 billion annually in the U.S. alone. With generics, that could have dropped by 80%. Instead, patients paid more, and Medicaid and Medicare picked up the tab.

But Is It Always Bad?

Not always. Some secondary patents lead to real improvements. The American Cancer Society highlighted a 2021 study showing new formulations of chemo drugs reduced severe side effects by 37%. That’s meaningful. And companies like Pfizer and Merck argue that follow-on innovation keeps patients safer and treatments more convenient. PhRMA, the industry group, says secondary patents fund $14.7 billion in annual R&D. They point to drugs that went from needing daily injections to weekly pills, or from causing nausea to being tolerable. But here’s the problem: only 12% of secondary patents, according to Harvard’s Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, offer any real clinical benefit. The rest? Routine tweaks. A new salt form. A slightly different coating. A new dose schedule that doesn’t improve outcomes-just keeps generics out.Global Differences: Who Allows It?

Not every country plays by the same rules. In the U.S., the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the system that lets companies list secondary patents in the FDA’s Orange Book. That’s how they trigger automatic 30-month delays when generics challenge them. India doesn’t. Section 3(d) of its 2005 patent law says you can’t patent a new form of an old drug unless it shows “enhanced efficacy.” That’s why Novartis lost its bid to patent the beta-crystalline form of Gleevec in 2013. Generics hit the market quickly. Brazil requires health ministry approval before a patent can be enforced. The EU demands “significant clinical benefit” for certain secondary patents. These are deliberate policy choices to keep drugs affordable. In contrast, the U.S. has no such requirement. A patent office examiner doesn’t need to judge whether a new tablet form actually helps patients-just whether it’s “novel” and “non-obvious.” That’s a low bar.

Ifeoma Ezeokoli November 30, 2025

Okay but imagine being a kid in Lagos and your mom can’t afford the $20k pill because some lawyer in Chicago filed 264 patents on a pill that’s basically the same as the one from 1998. 🥲 We don’t need more patents-we need more humanity.

Daniel Rod December 2, 2025

It’s wild how we’ve turned medicine into a legal chess game instead of a healing art. The original patent was meant to incentivize innovation-not to create a moat around a drug so rich people can keep cashing in while others skip doses. 🤔 Maybe the real breakthrough isn’t in chemistry… it’s in ethics.

gina rodriguez December 4, 2025

I’ve seen patients switch from generics to the ‘new’ version just because their doctor said it was ‘better.’ It breaks my heart. Sometimes the only difference is the color of the pill. 💙 We need better education and less marketing hype.

Sue Barnes December 4, 2025

These companies are stealing from sick people. No one should profit off suffering. If you’re not curing anything, you’re just exploiting a loophole. This isn’t capitalism-it’s medical predation. 🚫

jobin joshua December 5, 2025

Bro in India we’ve been fighting this for years! Novartis tried the same trick with Gleevec and got shut down hard. 🇮🇳 We don’t need fancy patents-we need affordable pills. Let the generics in!! 🤝

Sachin Agnihotri December 6, 2025

Wait, so a patent on a different crystal shape counts as innovation?? That’s like patenting the color of the box your phone comes in… and then charging $200 extra for it. 😅 I mean, if the FDA doesn’t even require proof it’s better… why are we even pretending this is science?

Diana Askew December 6, 2025

Big Pharma owns Congress. That’s why this is legal. The same people who made the laws are getting paid by the drug companies. This isn’t a loophole-it’s a rigged system. 🕵️♀️ And they’re lying to you about ‘innovation.’

King Property December 7, 2025

You all are clueless. The system works exactly as designed. If you can’t afford Humira, you shouldn’t be on it. The patent system incentivizes R&D-without it, we wouldn’t have ANY new drugs. You want cheap pills? Move to India. Or stop complaining and get a better job. This isn’t a moral crisis-it’s an economic one. And if you think generics are safer, you’re delusional. The manufacturing standards aren’t the same. Don’t be a naive idiot.